| One Renminbi Weighs This Much... | ||||

| By Lin Hui-fen and Hong Jun-da Translated by Tang Yau-yang Photos by Liao Zhi-hao | ||||

Chen Long (陳龍), 12, lives in Shimen-kan Village, Malutang Township, Luquan County, Yunnan Province, China. The area is in the mountains, 2,750 meters (9,000 feet) above sea level. An autonomous district for Yi and Miao peoples, Luquan is an officially designated “county of poverty,” one of 341 minority ethnic counties in the nation with this designation. Chen Long’s village is the poorest of the poor—it has been listed as a “village of absolute poverty.” Homes in the area, though electrified, do not always have a dependable supply of power. As a result, residents still mainly use firewood to cook and heat their houses. On this day, Chen accompanied his grandmother to a nearby hill to collect tree twigs and branches for fuel. He’s done this chore since he was seven. He swung his billhook at a tree branch. He can tell when a branch is dead and can be chopped off for firewood. “I check if all the leaves have fallen off, and I use my fingernail to dig into the bark,” he said. “If it’s still moist, it’s alive [and I’ll skip it]. Otherwise, I’ll cut it off.” After some more searching, he held down another branch and hacked at it. “Oops, wrong one—it’s still alive,” he said with embarrassment. “Perhaps it’ll survive the injury.” By this time, his grandma had already picked up a lot of dry twigs and branches off the ground. The two of them, carrying large piles of fuel on their backs, started down the hill. Every time Chen comes home from his boarding school, he helps his grandma gather enough wood to last two weeks. By the time the wood runs out, it’s time for him to return home and repeat the routine once again. “Grandpa’s sick, so he can’t help Grandma. Her feet hurt when she walks, so she needs my help,” Chen said. In addition to helping her collect firewood, he always helps his grandparents in the kitchen and he feeds the chickens and pigs. When they arrived home, his grandma prepared to cook dinner. Like other farmers in this area, they have just two meals a day. The boy fetched water and stoked the fire in the stove. Grandma made Chen’s favorite dish—potatoes cut into cubes and stir-fried until they were soft and tender. Breathing in the aroma, Chen exclaimed, “It smells so good. Grandma’s cooking is the best.” He feels that nothing beats seeing his grandparents in good health and having a meal with them.

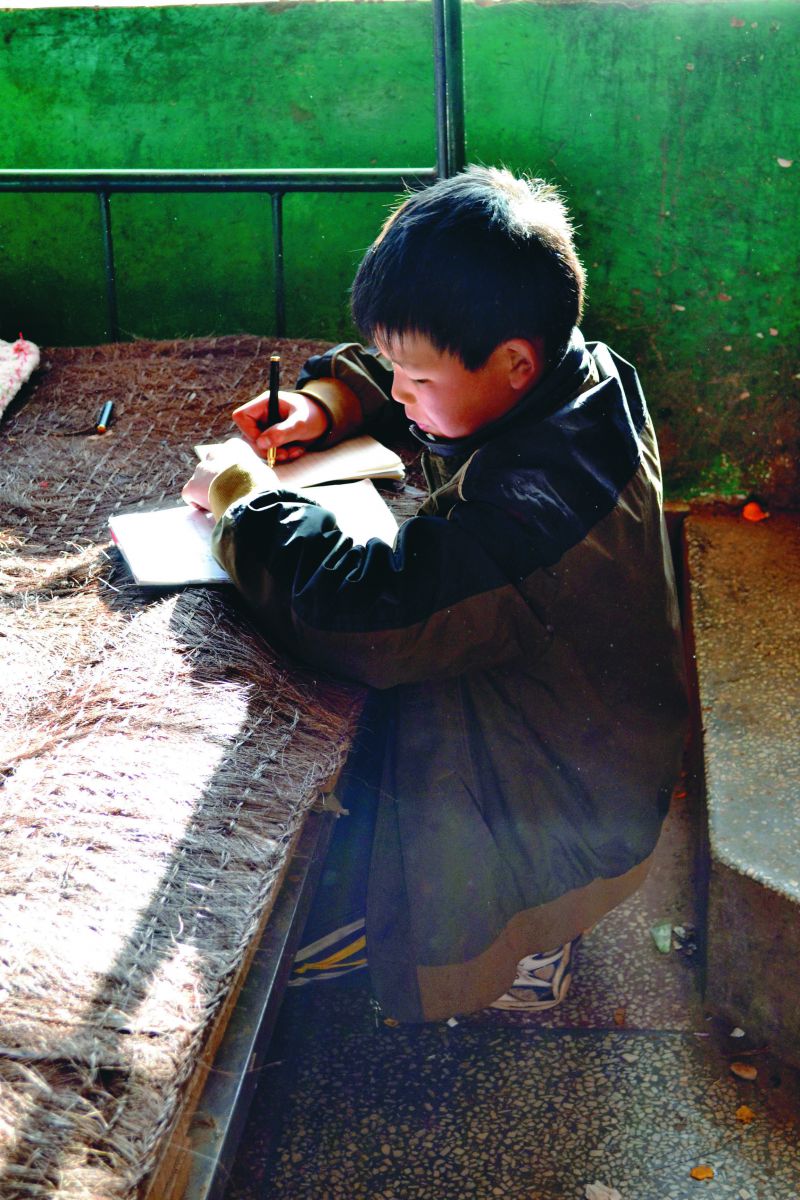

A hard-working boy Chen attends Malutang Central Elemen-tary School, which receives its students from various villages scattered in the nearby mountains. Chen’s village is about ten kilometers (6.2 miles) from the school. The fare for a bus ride between the village and the school is ten renminbi (US$1.60). To save money, Chen walks instead of taking a bus. It takes him about three hours to cover that distance over the mountain roads, so walking to and from school every day is impractical. Other students in the area are in similar situations. To help these students out, the school modified its calendar: ten consecutive days of instruction followed by four days off, during which students may go home. Like his schoolmates, Chen lives on campus, and he only goes home to be with his grandparents once every two weeks. That is why he makes sure that his grandparents have enough firewood to last two weeks before he returns to school. The temperatures in the mountains often hover around the freezing mark. Before starting a class, teachers even need to build a fire in the corridor outside the classroom for some heat. Yet the cold never seems to bother the kids. During recess, most of them go outside and play basketball or horse around. But not Chen—he stays in the classroom. He is a hard-working student, and between classes he does drill questions in his books. His grades put him in the top three in his class. According to his teacher, he is responsible though a bit introverted—he is taciturn even when he hangs out with his classmates. “When I’m alone,” said Chen, “I think about my problems. I like studying because it can improve my life.” When Chen was three years old, his father died. His uncle, Zhang Tianyong (張天勇), married his mother at that time and took over the responsibility of caring for him, his mother and his brothers. Chen’s older brother goes to senior high school in the Luquan county seat. That costs close to 10,000 renminbi (US$1,630) each semester for tuition, fees, supplies, and room and board. This is all on top of a mortgage that the family had to take out to rebuild their home after it was destroyed by an earthquake more than a decade ago. Chen’s parents have to work very hard to make the mortgage payments and to defray the cost of schooling for their three children. To make a living, they took their youngest child and moved to Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province. There they work and work, and they get to go home just once a year for the Chinese New Year holiday. As a result, Chen’s family is split three ways for most of the year. Though Chen is a very independent boy and he lives with his grandparents, he misses his parents and brothers. He expressed his longing for them in a drawing of his entire family visiting a park together. “This is Dad, Mom, and these are my brothers,” he pointed out. “It was Chinese New Year, and we were playing on the grass. There were fish in the stream. My kid brother and I had such a great time running after the fish.” That was the most memorable time that he had had with his family. His stepfather loves him very much. “Once when I was in first grade, my feet hurt a little and it was snowing,” Chen reminisced. “Dad carried me on his back the whole long way to school.” With moist eyes, Chen told us what he wanted to say to his father: “Thank you, Dad. I want to repay you for all you’ve done to raise me.” He continued: “Don’t worry, Mom and Dad, I’ll help Grandma at home. I hope you pay off the debt soon and come home to stay with me. I miss you very much. How I wish we could all be together.”

The weight of one renminbi Kunming has seen rapid economic growth in recent years, and high-rise buildings abound. Kunming University, in the northern part of the city, has a student body of 17,000. There are more than ten dormitory buildings, and Chen’s parents work in two of them. His father sits in a ground-floor room in the building where he works, waiting to take orders from students for bottled drinking water. When an order comes in, he carries the water on his shoulder to the student’s dorm room. These are not small water bottles—each holds 19 liters (5 gallons) of water and weighs 19 kilograms (42 pounds). Even just one such bottle of water would be heavy enough for most people, but he carries at least two on a shoulder pole. It would be great news for him if all his deliveries were made to rooms on the ground level, but he often needs to walk fully loaded up several flights of stairs. Sometimes he takes as many as four bottles in a single trip. For each 19-kilogram bottle of water that he delivers, he is paid one renminbi. He may deliver as many as 60 bottles to students on a particularly busy day. Busy or not, the day starts at eight o’clock in the morning and ends 12 hours later. When there is no business for him, he sits in his room waiting and watching students pass by, chatting, laughing, bantering, or doing whatever else students do. As he looks on, he, who only finished elementary school, thinks to himself, “I just hope my three children will grow up and become good people.” While Chen’s father hefts water bottles, his mother, She Youju (佘有菊), works in another dorm as a cleaning lady. She mops floors, washes windows, empties garbage, and performs other custodial duties. “We didn’t get much education, so we have no choice but to do menial jobs or heavy labor,” she says. That statement pretty much sums up their predicament. After a long day of hard work, the couple can finally get some rest. They have dinner with their youngest son, Xiaoguang (小光), in their rented room. It is less than 110 square feet and has no toilet or bathroom. The locals refer to these types of dwellings as “villages in the city.” Chen’s mother furnished the room with things that others had thrown out. This small room costs the couple 300 renminbi (US$50) a month, a good portion of their total income of about 3,000 renminbi a month. It takes the couple 3.3 months to earn enough money to put their oldest son through just one semester of high school. Imagine the burden they will face when the other two boys go to high school. Chen’s father knows that his boy at home misses them and is waiting for them to return. “If he gets admitted into a college, I’ll definitely put him through,” he said firmly. The tuition for college is 10,000 renminbi a year, for which he’ll have to deliver 10,000 bottles of water. “However hard it may be, we’ll support him.” So, for Chen, one renminbi weighs 19 kilograms, to say nothing of the weight of his father’s love for the family. The boy knows his parents love him, so despite his loneliness he studies hard. He believes that his education will one day lead him, and hence his parents, to better days.

|

|