| Pictures of Children |

| Text and photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa Translated by Tang Yau-yang |

The author of this article is a seasoned professional photojournalist. Over the years, he has taken countless photographs on assignment or otherwise, amongst which are many images of the children he has encountered. We featured six of those photos in our Winter 2013 issue. We feature some more in this issue, along with the captions that the photographer himself wrote. Ten Thousand Whys Guizhou, China, 2005

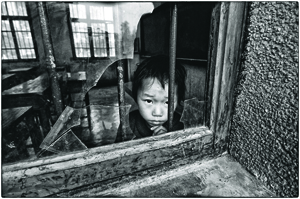

The recess bell had no sooner rung than the children, books in hands, stampeded towards a classroom with barred windows. The room they were headed for functioned as the school library, and the children were rushing to return books. The scene reminded me of a run on a bank. The room was about 360 square feet, sparsely occupied here and there by a small number of books for young readers, in just a few genres. The most common book in the library, by volumes held, was Ten Thousand Whys, a popular science book for children. I read that book when I was little, almost half a century ago. I was a little surprised to come across it again in this elementary school in a remote mountain region of Guizhou, southern China. Unlike typical libraries, it had no open shelves stacked with books. Instead, students had to borrow or return books through a barred window. On one side of the bars, throngs of students jockeyed for position. On the other side—in stark contrast to the chaos outside—a librarian was taking his time serving his customers. Perhaps the crowds and the hustling were just part of the job for the librarian: It had always been this way and would perhaps always remain the same. The students appeared to be inured to it, too. Jostling and hustling in order to learn, to acquire knowledge, was nothing to them. I was reminded of a famous ancient Chinese poem: “Only after experiencing bone-chilling cold can a plum flower exude real fragrance.” [A Western saying that conveys a similar meaning is: “No pain, no gain.”] Less attuned to such local thinking, I kept asking myself, “Why?” Why did the school library have to operate like that? Why didn’t the librarian quicken his pace? Why didn’t the school train the children to wait in line for service? Why should getting a book to read be so laborious and trying? I couldn’t help wondering if managing a library in such a way pumped up the students’ desire to read—or diminished it. Perhaps it had never occurred to the school administrators to find ways to improve the situation because they had never felt anything was wrong here. My many questions would probably never be answered and would forever be left hanging in the air. What’s On His Mind? Guizhou, China, 2006

Wang Xiaoming [王小明], not his real name, was a second grader at an elementary school nestled in the mountains of Luodian, Guizhou, China. Perhaps you wonder what the story was behind the gloomy, pitiful expression on his face in this picture. I visited his school with Tzu Chi volunteers in December 2006 to distribute relief goods. After the distribution, we asked a teacher to recommend a student from a needy family so we could write a report on the case and help people get a better understanding of local poverty. The teacher recommended Wang Xiaoming. Poverty had forced his parents to work out of town. The family had not heard from them in years and didn’t even know whether they were still alive. Xiaoming lived with his aged grandfather. On school days, after school let out at noon, the boy had to go home to cook lunch for the old man. After describing the circumstances surrounding the Wang family, the teacher called out to Xiaoming and told him to take us to his home after school that day. The boy said nothing in response. He only listened to her with a vacant look on his face. We returned to the classroom at noon, ready to go visit the Wang household. When the students were released from school, they all rushed out of the room happily—with the exception of Xiaoming. He alone remained fixed to his seat, showing no intention of going anywhere. Seeing him sitting there, the teacher cried out to him, “Xiaoming, aren’t you going to take the visitors home to see your grandpa? Why aren’t you going?” The boy said nothing in return, only staring at his teacher and at us. He looked very much like a cornered animal at that moment, anxious and on edge, trapped in a classroom where there was no place to hide. The boy’s silence only spurred the teacher to talk even more loudly and urgently. Still, Xiaoming remained silent. Over ten minutes passed in the standoff. All the other students had gone home, leaving the campus almost empty. Xiaoming, the teacher, two Da Ai TV workers, a print reporter, and I were the only people remaining in the classroom. The air became a bit suffocating as we stood there awkwardly. We eventually told the teacher that we would not impose on the boy. Perhaps we could find another case elsewhere. With that we said good-bye to them and stepped out of the classroom. When I looked back, I saw Xiaoming standing by a broken window looking out at us. It seemed like he wanted to say something, but he bit his tongue. In that instant, the photographer in me jumped to life. I took out my camera and snapped six shots in a row. We kept a tight schedule during our trip to Luodian, so I had little time to think much while on the scene. Soon, the Xiaoming episode was gone from my mind. It didn’t come back to me until I had returned to my office in Taipei. Working through the shots that I had taken during the trip, I saw the photos I took of Xiaoming. His innocent face brought back memories of that day in his classroom and of my own school days when I was his age. Back in my time, a teacher was a figure of absolute authority, whose directives a student simply carried out without a second word. A student had no reason, much less the guts, to say “no” to a teacher. I know that at the mountain school Xiaoming attended, a teacher was still as much a figure of absolute authority as back in my days. Disobeying the teacher was regarded as an extremely serious offense, an absolute taboo. When a student chose to behave like that, he most likely was under some kind of pressure to do so. What then was the pressure that Xiaoming was under? Was it because he felt too ashamed of his poverty to show his home to strangers? Was it because his grandfather had told him to never take other people home? Or was it for some other reason that he simply didn’t want to make public? Only Xiaoming knows for sure.

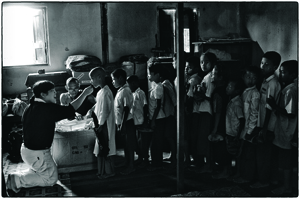

Those Pesky Worms Yangon Province, Myanmar, 2008

Cyclone Nargis devastated southern Myanmar in 2008. In its aftermath, the Tzu Chi Foundation distributed relief supplies and provided other aid in the disaster areas. When volunteers were giving out school supplies at a rudimentary elementary school located in a temple, I saw a Malaysian volunteer, a medical worker by profession, kneeling on the floor, feeding the students roundworm medicine. This sight warmed my heart and took my mind back to my childhood, half a century ago. It was a time of malnutrition and poor hygiene. Roundworms were common among children, including my siblings and me. Occasionally, my mom would buy a kind of sweetened medicine to expel our parasites. But the medicine was not the only way she dealt with the worms. From time to time, around midnight in the depth of winter, she would peel away the covers under which my siblings and I were sleeping together, turn us face down and butt up, and remove our diapers or pants. Then, one child at a time, she separated our buttocks, looking for roundworms or other kinds of parasites lurking there. If she saw any, she picked them off one by one. Roundworms were bigger and easier to get rid of, but some parasites wiggling in that area were but half a centimeter [four tenths of an inch] long and not much wider than a hair. It was quite an undertaking to get rid of those pesky, teeny worms, but Mom always carried out that abominable, time-consuming task patiently and meticulously. As the time dragged on, we kids, still heavy-eyed, couldn’t stand the cold and would keep asking her, “Mom, are you done? It’s freezing.” I’ll never forget that cold. That was half a century ago. My mom has been gone now for almost 20 years. I don’t know why, but as I recall those bone-chilling nights long ago, a warm glow still fills my heart. I wonder: Thirty years from now, will any of the students in this photo remember us foreign visitors, who once visited their homeland and did this seemingly trivial thing for them?

Instant Noodles Guizhou, China, 2005

It was time for lunch at an elementary school tucked away in the mountains of Guizhou. At the sound of the class bell, students swarmed to a store next to the school to buy lunch. It isn’t easy to get around in the mountains, and their homes were far from school, so the students usually took care of their lunches this way. Lunch was generally instant noodles that sold for one renminbi [16 U.S. cents] a pack. The store owner supplied a bowl and hot water to soak and soften the noodles. However, so many students were buying noodles that the store owner could not keep up with the demand for hot water. Many students were forced to use lukewarm water instead. The crisp, crunchy noodles would not easily become soft when soaked in such water, especially in the cold weather, but given their poverty and the general scarcity of goods, the children just had to make do. Hot water or not, the students wolfed down the noodles all the same. I don’t know whether it was because they were starving, or because the seasoning pack had piqued their appetite. Perhaps it was both. For these children, the noodles were not snacks but their lunch, a main meal of the day, a meal that they had to have to sustain them. I have never eaten that kind of instant noodles, so I don’t know what they taste like. But I do know that while the cheap noodles could somewhat fill a stomach, they offered little else to the eater. They provided little to no nutrition—nutrition which these growing children badly needed. The sores at the corners of their mouths and the discolored patches of various sizes on their faces gave away the fact that they suffered from malnutrition. They were obviously deficient in vitamins, a friend on that same mission told me. These children might be as medically naïve as I, so they didn’t know the nature of the problem that they were facing. Even if they had known, they couldn’t have done anything about it. Their fate is a cruel reality—sometimes life leaves you with no choice. I didn’t ask my friend to tell me the consequences of vitamin deficiencies; I wasn’t all that eager to find out. Looking at this picture now, I suddenly think of a propaganda film I once saw which described how food worth many hundreds of millions of renminbi has been wasted in China every year in recent years. I wonder what those kids who ate instant noodles for lunch would think if they saw that film.

Little Butterfly Guizhou, China, 2005

That basket filled with firewood was really heavy. I tried it. It weighed more than my bag fully packed with photography gear—cameras, lenses, and all. And yet, this little girl was able to carry the basket on her back, negotiating the gritty paths in the mountains with ease and agility. I had to hustle to keep up with her. She was not training or in a PE class. Instead, she was gathering firewood with which her family could cook and boil water. This was a daily routine for children in the area. They did it before or after school. This mountainous area of Guizhou had little in the way of transportation and natural resources. The land was barren. People made do with what was available to them, which they ferried home on the backs of animals—or themselves. Things being what they were, children grew up expecting to work. They had known since they were very young that nothing could be had without labor. I didn’t pity the little girl, however. Quite on the contrary, I envied her. I envied the way she and her friends traversed the mountain trails with such ease and grace, like butterflies, their laughter echoing across the skies. The big mountains had nurtured in the local people minds as open as the valleys, and they possessed a “truth” that represented humanity at its most sincere. We outsiders could easily feel it. Life is not all sunshine; sometimes it is cloudy and rainy. When the children got tired from their work, they rested and then set out again. The local people labored and received from nature what they needed. They never needed to worry about energy problems such as whether nuclear power plants should be abolished, nor did they need to please their bosses to advance their careers. In this way, they possessed peace of mind. I envied them for that.

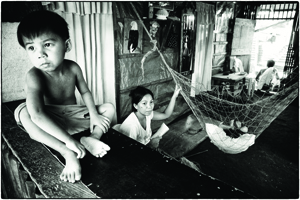

Dreamland Boy Rosario, the Philippines, 2011

I used to believe that children, whatever their background or wherever they lived, were largely immune from their environment: As long as they weren’t hungry and had friends to play with, their worlds came alive. I drew that conclusion from my own experience as a child, and I thought that it was the truth the world over. But this long-held presumption of mine was debunked when I saw the expression on the face of the boy pictured here. He lived on a remote shore in the Municipality of Rosario in Cavite Province, Philippines, about a 90-minute drive south of Metro Manila. Perhaps because of a lack of government control or for some other reason, a dumping ground for the city’s waste had formed beside the boy’s home. Mountains of garbage emitted a repulsive stench. Dirty, foul-smelling fluids ran in all directions from the piles. The garbage attracted not just swarms of flies, as big as bees, with red heads and golden bodies, but also scavengers who picked out things from the rubbish to sell. They had built makeshift homes nearby because there seemed to be no housing regulation—they could just build at will. Illegal dwellings built of salvaged plywood and corrugated metal sheets had popped up one after another in the vicinity of the dumping ground. This boy lived in one of those shanties. When you don’t have two pennies to rub together, having a place to live is good enough, wherever that place might be. The inconveniences of having no running water or electricity, as well as having to put up with air pollution and poor hygiene, don’t matter that much as long as you have a roof over your head to protect you from the elements. He lived in a village named Dreamland. It was such a pretty name that one really hated to look at the reality. |

|