| Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital: Excellence in Catheterization | ||||||||||||||||||

| By Huang Xiu-hua Translated by Tang Yau-yang Photos by Yan Lin-zhao | ||||||||||||||||||

Artery Open, Leg Saved When the clogs are cleared and blood flows again into the leg, the patient is surprised and delighted by the warmth that returns to the cold limb. Dr. Huang Hsuan-li has performed peripheral vascular interventions for ten years, sparing about 700 patients the physical and mental agony of having their legs amputated.

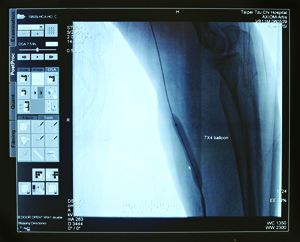

In the ten years that Dr. Huang Hsuan-li (黃玄禮) and his team have engaged in peripheral vascular intervention, 889 legs have been saved. Instead of amputation, 690 patients have regained the use of their legs as a result of the treatment. This represents an amazing success rate of 96 percent for the doctor and his team. Huang was promoted to the rank of attending physician in 2002. Just two years later, while he was working at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Professor Wen Ming-shien (溫明賢) assigned him to the field of peripheral vascular disease (PVD, also called peripheral arterial disease). The treatment for PVD is called peripheral vascular intervention (PVI)—that is, opening up blockages in blood vessels in the legs to save them from being amputated. Peripheral vascular intervention When Huang first started treating patients for PVD, he chose only those whose prognosis was particularly poor. Some of them had been confined to wheelchairs because occlusions in their legs had reduced blood flow to tissues there long enough to cause damage and result in conditions such as skin ulcers. The worst cases had to have their limbs amputated. Huang did not originally have high expectations for his interventions, which consisted of using catheters to open up circulation in peripheral blood vessels, especially those in the lower extremities. Those blood vessels are typically plagued by plaque build-up. However, he was surprised by the marked improvement in some patients after treatment. For example, one man who had been wheelchair-bound before the intervention walked unassisted into Huang’s clinic after the procedure and exclaimed, “Dr. Huang, I can walk now!” Huang was overjoyed. He was thrilled beyond words. His confidence in the procedure surged. Shi Chun-ren (施純仁), now in his 60s, was one of Dr. Huang’s first patients. When he first met Dr. Huang in 2004 at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, he had been suffering from diabetes for more than ten years. Poorly controlled glucose levels had led to many complications. He had been on kidney dialysis, and he was suffering from PVD. As a result, his left leg had already been amputated. He was seeing Huang because his right leg was cold and numb. He feared that he would soon lose that leg too and would have to spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair. That prospect left him extremely depressed. The doctor employed percutaneous transluminal angioplasty to treat Shi. He inserted a balloon catheter on a guide wire into Shi’s right groin and then maneuvered it to the narrowed artery in Shi’s leg. He inflated the balloon to push the accumulated deposits against the artery wall. With more blood flowing through the widened artery, Shi once again felt warmth and sensation in his leg. When Dr. Huang moved to Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital in 2005, Shi followed him. The doctor gave him five more PVI treatments after the move and eventually saved the leg. Shi has been Huang’s patient for a decade now. “It’s so nice to feel the leg warm to the touch again,” Shi exclaimed. “Thanks to Dr. Huang, my right leg has ‘lived’ an extra ten years now.” He said that were it not for the doctor’s patient and careful treatment, his leg would have been sawn off long ago. “Though I can never move around as freely as ordinary folks can, I still have the use of one leg. I can at least take care of myself and live with more dignity.”

Challenges along the way The same principle underlies both peripheral arterial and cardiac catheterizations, but because of the differences in the lengths and widths of the blood vessels being treated, there are different requirements for the instruments used. Cardiac catheterizations were much more widely performed when Huang started performing catheterizations on lower limbs. Peripheral catheterizations took much more time to perform than cardiac catheterizations, but received only a quarter as much reimbursement from the national health insurance system. As a result, hospitals were generally not as interested in offering non-heart catheterizations. That made it difficult to procure the equipment—catheters, balloons, and stents—for peripheral catheterizations because with such a small market, few businesses were interested in importing them. Huang, therefore, encountered many setbacks by focusing on peripheral instead of cardiac catheterizations. “Using cardiac catheters to treat blockages in lower limbs just does not work well,” Huang explained. “The farthest a cardiac catheter needs to reach is seven centimeters [2.8 inches], but a catheter for the lower extremities needs to reach 100 centimeters [39.4 inches]. The shank alone is 30 centimeters [11.8 inches]. When I first started, the longest balloon available in Taiwan was but four centimeters [1.6 inches]. Using such inadequate equipment made our treatment not just time consuming but also ineffective.” Similar problems with the stents also plagued Huang. Because suitable instruments were not readily available, it was inevitable that some patients still had to undergo amputations. But Huang remained undaunted. He did not quit his PVI treatments, which he believed to be a better and safer alternative to the much more invasive and dangerous bypass surgery.

Always learning Though the equipment seemed to pose a major problem, Huang often asked himself when he ran into difficulties treating patients whether they were caused by inadequate instruments—or by his limited capabilities. Hurdles in treating patients prompted him to attend conferences and training courses abroad in order to learn new techniques. In 2007, he learned the latest PVI techniques at a conference in Italy. In 2009 he traveled to Germany at his own expense to study for three weeks at Park Hospital Leipzig, a heavyweight institution in the world for the treatment of peripheral vascular diseases. Huang remarked, “That hospital had a wealth of clinical experience from treating more than 4,000 patients a year. We in Taiwan were just beginning in that field. They were far and away better than us.” Park Hospital Leipzig also boasted topnotch talents in the field. “Dr. Andrej Schmidt was the best among the best,” Huang said of his teacher there. Huang learned much in this enriching environment. Experiences like this helped him realize how vast the field was and how much he had yet to explore. Each time he returned to Taiwan, he brought back not just new procedures but often also information about the equipment necessary for those procedures.

In Leipzig, Huang took time to write down identifying information about the instruments that the doctor used in the procedures that he was observing. After the doctor had finished the procedure, Huang would go through the garbage cans to pick out the packaging materials for the instruments that the doctor had just used, then he would call and pass on the information to staff at the catheter lab at Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital. They in turn would work with local trading companies to import those instruments. Through efforts like these, Huang has built up his store of equipment to treat patients with various needs. The last thing that he wants is for a patient to lose a limb because some instrument is unavailable. Medical equipment and instruments undergo frequent updates and renewals. When Huang gets a new instrument, he first uses it only on patients whom he has carefully screened. Then he observes the results for three to six months. “I’d typically observe five to ten patients,” Huang noted. “Only after I’m satisfied with the results will I recommend an instrument to more patients.”

Dedication to the field Huang closely follows up on his patients to improve the efficacy of his treatment. He pays close attention to every case he handles, making bold hypotheses and carefully proving or disproving them. Such observations and follow-ups take time but help him gain in-depth knowledge every step of the way throughout the entire PVI cycle. His long-term follow-ups allow him to accumulate much experience and better devise comprehensive plans for treating PVDs. This has helped make him an excellent doctor.

The efforts that he and the rest of the PVI team have put forth over the years have catapulted Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital to the top tier of hospitals in Taiwan in the treatment of peripheral vascular diseases. Patients have flocked to the hospital for high-quality care. Huang Chun (黃純), 105, is the oldest patient Dr. Huang has treated. At first the doctor worried that because the patient was so old, her blood vessels might have aged to such an extent as to affect the efficacy of treatment. However, a checkup revealed that her blood vessels were as good as those of a person in their 80s. Dr. Huang performed a PVI, and her toes were no longer black and cold. She was all smiles, and her granddaughter even exclaimed, “It’s a miracle!”

Liu Zhang Qiu-ling (劉張秋苓), 88, had a PVD that resulted in a vascular ulcer on the big toe of her right foot. Because she was not diabetic, she was at first diagnosed with athlete’s foot and treated accordingly. But her condition continued to worsen and the ulceration spread. She was in so much pain that she could not walk. She lost her appetite, slept poorly, and became very depressed. When she was finally properly diagnosed with PVD, her doctor at the time decided to use balloon angioplasty to fix her problem. However, just 20 minutes into the procedure, he walked out and informed the family that he was unable to carry on because of the patient’s advanced age and the serious blockages. Later, the patient sought help from Dr. Huang. Due to the severity of her condition, Huang decided on a two-phase treatment. On the day the final procedure was finished—two weeks after the first two procedures—the patient said she was no longer in pain. She could even get out of her bed and walk around. She was discharged from the hospital the next day. Before she left, she walked on her own into Huang’s clinic to say goodbye. “That’s the marvel of medicine,” Huang said, “and that’s what gives physicians the biggest shot in the arm. It just amazed me to see the treatment transform Mrs. Liu and make her mobile again.” And Liu was not the only one who benefited from the treatment. Peace of mind returned to her family—they no longer had to worry so much about her and could carry on with their lives. Liu deeply appreciated Dr. Huang’s efforts, and his hard work was not lost on her. “It was about eight in the morning when Dr. Huang started the final procedure on me,” she recalled. “I lay on the operating table wide awake. He stood there working on me until two in the afternoon. Standing for so long, his lower back and feet must have been awfully sore. It hurts me to just think of that.” Besides being a doctor with good skills, Huang is extremely patient in working with his patients and their families. “Dr. Huang is very affable,” said Liu’s daughter. “He always responded to our questions in detail, and he was especially patient with my mom. He never got tired of answering all her questions. He’s truly a conscientious and loving doctor.”

It’s all worth it Through years of learning, dedication and breakthroughs, Huang and his team have raised their success rate from 87 percent to 96 percent: For every 100 limbs on which they work, 96 are saved from amputation. Such success, however, has not come without sacrifice. During a PVI procedure, a physician must wear protective gear to help shield him or her from too much exposure to radiation. A lead vest and skirt together weigh about six kilograms (13.2 lbs.). An older version even weighed as much as ten kilograms (22 lbs.). “The weight of the lead stresses the shoulders and the pelvis. The longer they are under stress, the more seriously they are damaged,” explained Huang. Each catheterization procedure lasts between two and six hours. Wearing so much weight for such a long time can exact a big toll on the doctor’s body. In addition, when physicians perform such a procedure, they often need to stare at computer screens with their full attention and unconsciously tend to lean forward. Maintaining such a bad posture for long stretches of time easily leads to injuries in the joints, ligaments and tendons. Huang has been doing this for ten years. During that time his cervical vertebrae—the bones in the neck—were hurt twice: three years ago and again a year ago. In addition to the pain, his mobility was severely affected. He only recovered after a period of care and recuperation.

Despite his injuries, he has not a word of complaint. After all, he himself chose this profession. Besides, the joy that comes from seeing improvements in his patients makes all of it worthwhile. “I derive the greatest joy from that, and it has given me the strength to stay the course,” he said. He clearly knows the significant value of saving a leg from being cut off—it means a lot not only to the patients themselves but to their families as well. The positive impact just cannot be overstated. Seeing the value in his work, Huang has never regretted shifting from cardiac catheterization to peripheral vascular catheterization. “There are plenty of physicians in Taiwan doing cardiac catheterization—one fewer doctor won’t matter. However, there are so few of us doing PVIs that each of us has added value for our existence.” He further pointed out that diabetes, which is linked to vascular disease, afflicts no fewer patients than does heart disease, and that complications from diabetes can be just as deadly. Therefore, there are real unmet medical needs for physicians like himself to strive to serve. This is yet another reason why he keeps pushing ahead. Over the years, Huang has encountered his own share of medical setbacks. The vascular occlusions in some patients were so firm and well established that he could not even put a catheter through. There were also cases where even after blockages had been opened, serious infections still led to the removal of parts of limbs where gangrene had set in. Huang clearly remembered a patient in her 70s whom he treated in 2005. The initial treatment saved both of her legs, but later, when an artery in her left leg clogged up again, Huang failed to pull off another successful catheterization. Worse, the procedure caused a thrombosis (when a blood clot blocks an artery or vein), and even after the patient’s whole leg was amputated, she still passed away. Huang could not hold back his tears when he talked about the patient. Though the patient’s family did not blame him and instead even cheered him on, encouraging him to use that experience to serve the next patient better, Huang still could not help thinking, “If I had been more circumspect and more skillful, would it have turned out differently?” His skills today are nothing like his skills those long years ago—his proficiency has greatly improved. Even so, he still thinks of that female patient and reminds himself to do his very best with every patient. “Every life is precious,” he affirmed. “Confidence comes with tears and sweat.” Huang believes that he would not be where he is today without the patients who gave him opportunities to perform on them. “My patients are really my teachers.”

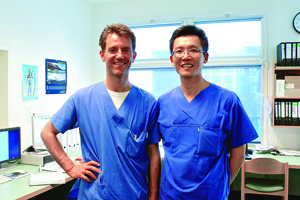

Many more legs to save Of the 1.5 million diabetes patients in Taiwan, about 20,000 have suffered from ulcerations in their legs, and 10,000 have had amputations. The latter number is shockingly high to Huang. His clinical experience tells him that PVIs could have saved about 90 percent of those PVD patients from amputation. But herein lies the problem: Not enough physicians in Taiwan are trained to do PVIs. There are only three attending physicians at the peripheral vascular center at Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital: Huang, Zhou Xing-hui (周星輝) and Wu Dian-yu (吳典育). At the most, the three of them together can treat 360 patients per year. Many more PVI specialists are needed to bring the amputation rate down. Though hospitals in Taiwan are equipped with ten times more PVI equipment today than ten years ago, it is still inadequate to handle the rapidly growing patient population suffering from PVDs, many of whom have yet to be identified as such. Many medical doctors are not even familiar with PVI yet. Huang therefore sees an urgent need to spread the word on PVD and PVI in order to save more people. To do that, he has published quite a few articles in professional journals and often spoken at medical workshops. One of the reasons why more PVI was not done in Taiwan was its relatively low level of reimbursement from the national health insurance. Huang has worked with two cardiology societies in Taiwan to lobby for higher reimbursements, and they have succeeded. Though the raised insurance payments are still not even half as much as those for cardiac catheterizations, Huang hopes that the new reimbursement rate will attract more practitioners to the specialty.

Still more to do Huang said that when he first started in this field, he didn’t have a clear sense of the direction he should take. But after all these years at Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital and after all the work he has done, he feels like a ship coming into port. Many of his dreams have been fulfilled. For example, he has helped acquire a full complement of equipment of all sorts and sizes necessary to treat all kinds of cases, and his comprehensive follow-up system has helped improve the success rates of interventions. All this would not have been possible without the full support of the hospital. He is only 46, and he and his team hope to do more. They want to further hone their proficiency in using PVI to treat occlusions in lower limb arteries and deep veins, and they also want to apply the procedure to superficial veins, a newer frontier for them. When they achieve what they hope to achieve, Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital will be able to provide care for more patients from head to toe, from artery to vein, from deep vein to superficial vein.

A Message to Diabetics As told by Huang Hsuan-li If you are a diabetic, you must first get your blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol under proper control. Do not smoke. If you have had diabetes for more than ten years or, if you are more than 50 years old and have had diabetes for four or five years, it is best that you have a doctor check the blood vessels in your legs once a year. If indeed there is a problem, follow the doctor’s advice in medication and exercise. If your condition is more advanced or you have had the disease for a longer time, you need to watch out for neurological and other vascular diseases, too. Remember to wear shoes that cover your entire feet to prevent foot injuries. Be sure not to cut the skin when you clip your toenails. Ordinarily, a small cut in the skin will heal in four or five days. If your wound does not heal within two weeks, it is best that you seek medical help to check your blood vessels. |

|