| Caught In a Predicament | ||||||||||||||||

It is reasonable that most people shouldn’t have to hide from the law, that their children can receive an education, and that they can obtain medical care when they are ill. But for Burmese refugees in Malaysia, such hopes are beyond their reach. Unable to return to their homes, they can only do their best to survive in a foreign land. It is still dark outside, but many people are already working and sweating at a large wholesale market in Selayang, near Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. Goods come into the market from all over the nation and are then distributed to vendors or restaurants. Most of the laborers who help move the huge quantities of produce and goods here are foreigners.

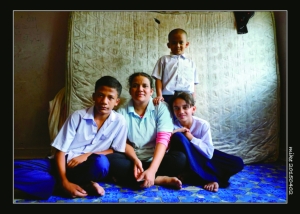

Statistics from the Immigration Department of Malaysia show that about five million aliens work in the nation. They mostly come from 12 nations, including Thailand, Indonesia, India, Vietnam, and Burma (also known as Myanmar). About half of them work illegally because they have overstayed their visas or because they are refugees. Though it is a Saturday, it is not a day of rest for some people, and certainly not for Dawtsung’s husband, a Burmese refugee who starts his workday at the Selayang market bright and early. He makes 40 ringgits (US$10.63) a day as a laborer. Dawtsung has been in Malaysia for more than two years, but she still speaks no Malay. She cannot carry on a conversation with local people, and she worries about running into the police. Consequently, she rarely goes out, and then only when she has no other choice. There are eight people in her family. They live on the third floor of an old apartment building in Imbi, Kuala Lumpur. The landlord partitioned the apartment into three units, one of which Dawtsung rents. The unit measures 180 square feet. Though the space is small, the rent for it is not. At 800 ringgits (US$210) a month, the apartment is a very heavy burden for them. With a daily wage of 40 ringgits, Dawtsung’s husband has to work 20 days a month just to pay the rent. Given these hardships, why did they leave their homeland in the first place?

Persecution Burma is home to 135 ethnic groups. The Bamar (or Burman) is by far the most dominant group in the nation, comprising about two thirds of the population. Other major groups include the Shan, Karen, Chin, and Kachin. The military regime that took power in 1962 forced minorities to move military supplies, build roads, or put up military installations, all without pay. There have even been many reports of systematic rapes of ethnic minority women by soldiers. Persistent oppression has led some minorities to resort to military resistance. Ethnic rebellions have erupted frequently, forcing members of minority groups from their homes. They have fled into neighboring nations, such as China, Thailand, and Malaysia. For example, the most recent conflict flared up in February 2015 in the Kokang Self-Administered Zone, located near the border of northeastern Burma and Yunnan Province in southwestern China. Tens of thousands of people fled to China to escape the fighting between government forces and rebels.

Andrew Laitha, chairman of the Alliance of Chin Refugees (ACR), said, “Refugees used to rush into India, so the Burmese military tightened border control there. Then they went to Thailand, but they were turned back to the Burmese army on the border. Now they are choosing Malaysia as their destination.” The refugee population in Malaysia has been on the rise for the last ten years. According to Yante Ismail, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) spokesperson in Malaysia, there are about 150,000 refugees in the nation, of whom 140,000 are from Burma. Those 140,000 include more than 50,000 Chin, 43,000 Rohingya, and 12,000 other Muslims. The rest are from other minority groups. Dawtsung’s family is an example of the largest group of refugees. Members of the Chin minority, long persecuted in Burma, they came to Malaysia in hopes of a better life. Sadly, the reality in their host country has not been rosy. Though refugees like them have become an important source of labor in Malaysia, Malay society has not accepted them. In fact, they are outright illegal. Unfortunately for them, Malaysia was not a signatory of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. The nation does not recognize refugees of any kind. It treats all refugees as illegal entrants and thus grants them no asylum. As a result, the Burmese expatriates find themselves in a predicament: On the one hand, they need to find work to support themselves and their families; but to work, they must expose themselves to public view and thus risk arrest or interrogation by police or immigration officials. However, they have no choice. Chin refugees have formed many self-preservation groups in Malaysia. They issue ID cards to their members and collect nominal fees to help new Chin expatriates obtain medical care, settle down, or apply to the UNHCR for asylum. Dawtsung heard about the Chin Refugee Committee (CRC) from friends and went there to seek help. The committee was ensconced in an old apartment building. Even though it was broad daylight, the curtains were drawn in the narrow space to keep out prying eyes. The CRC needs to lie low and avoid attention because it is not legal in Malaysia. “In Malaysia, there’s nothing legal about refugees,” said David, head of the CRC.

“Many refugees apply for memberships at various refugee organizations, seeking multiple layers of protection,” said ACR chairman Laitha. “They really want to make sure that somebody will be there to help them when the need arises.” However, the truth is that the membership cards, no matter how numerous, offer no substantive protection. What refugees really want are refugee cards issued by the UNHCR. If they are unfortunately caught by the police, presenting a refugee ID card issued by the UNHCR may get them off the hook. Even if this ID card does not prevent an arrest, the UNHCR will intervene to bail the refugee out. Given the importance of this card to them, thousands of refugees line up every day outside the UNHCR office in order to get one. It may take up to three years for an application for refugee status to be granted. Despite the long wait, the card is their only protective shield against law enforcement personnel in the nation, and it represents their only hope of being placed in another country. It is no wonder they endure whatever it takes to get one.

Children’s needs Before they can secure a better future for themselves, refugees have to struggle to find a way to survive in Malaysia. But eking out a living is not their only problem. Refugees soon find that since they are not legal residents in Malaysia, their children cannot attend public schools. That is not good. Without an education, their children are more likely to end up working at hard labor, even if they are one day resettled in another country. To help solve the problem, Chin people, with assistance from Christian churches, have set up community educational facilities which offer classes on such basic topics as English, Malay, and math. For example, the Talala school is located in a low house in a serene community. Small rooms equipped with chairs, desks, and chalkboards serve as classrooms. “We currently have a hundred students, 80 of whom live here. Nine teachers serve at the school,” said Principal Jacob. Jacob is himself a Burmese refugee. He, his wife, a son, and a daughter live in the school. At bedtime, chairs and desks are pushed to the sides of the classrooms, and residents sleep on the open floors. Jacob’s daughter is a student there. His wife, besides taking care of their son, who is just learning to walk, also looks after the students, who have been all but forgotten by the world. Dim Saun, 17, was teaching the students how to count when we visited the school. She was a graduate of the school and a current student at the Ruke Education Centre. She had a little spare time, so she returned to help. Schools like Talala only offer elementary courses. When students have completed those, they often have a hard time finding a suitable school to continue their schooling. As refugees, they are not accepted by public schools, and their financial situations put private schools out of reach. In response, the refugees, again with help from a Christian church, started the Ruke Education Centre in 2011. “[With further education provided by the center], I believe that students will have better chances of being placed in a third country. This is their hope for a better future,” said Principal Jacob.

The education center charges only nominal fees from students, with the church subsidizing the rest of the costs. The man in charge of the center, Michael, also teaches in college. “Children of any ethnicity can apply for admission to the school,” he explained. “However, only those who have passed an English proficiency test will be accepted. They need to be proficient in English to keep up with the instruction.” A Christian of Chinese descent, he takes care of the students as if they were his own children. He says, “I consider educating these students my responsibility.”

Floating refugees International human rights organizations have often described the Rohingya people of Rakhine State (also known as Arakan) in Burma as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world. There has long been friction between these Muslims and the Buddhist majority of Burma. They have even been denied the freedom to exercise their religion. They are prohibited, for example, from performing their five daily prayers. As if perpetual religious persecution were not bad enough, the Burmese government does not even recognize the existence or legitimacy of the Rohingya people. In 1982, it stripped them of their nationality and began to use them as forced labor. It comes as no surprise that they do not want to stay in Burma. Recently, Rohingyas fleeing that country have created one of the largest exoduses of refugees in Southeastern Asia. Many have tried to find their way into Malaysia, where Islam is the state religion. On May 11, 2015, three boats in which human traffickers were carrying more than a thousand Rohingyas reached the shallow waters off the resort island of Langkawi, Malaysia. At the same time, several other vessels were drifting off the coasts of Malaysia and Indonesia, having been denied entry into those countries. As the boats ran low on fuel, the traffickers abandoned them. Several thousand refugees were left floating at sea with very little food and drinking water. At last, Malaysian and Indonesian police took them onshore and put them into detention centers. The police estimated that boats holding about seven thousand more people were still drifting at sea, and there was no telling if they would be allowed onshore. Even though the Rohingyas know the Malaysian government will not give them asylum, they are still trying to get into the country. Once they are in Malaysia, however, they, like the Chin people, face the same daunting reality that they are illegal, that they cannot legally work, and that their children cannot attend public schools. But unlike the Chins, they face an additional obstacle: They don’t have the help and support of any church. The Islamic community generally has not yet extended a hand to the Rohingyas in Malaysia. Refugees without legal identities are like duckweed, having no root. Drifting with the wind or the current, they do not know where they will end up. Will they ever find a home?

|

|