| Education Is Precious, But School or Work? | ||||||||||

They are children of refugees in Malaysia. Should they work to help with family finances, or should they take on schooling expenses now to be better prepared for tomorrow? It’s a difficult choice for parents, but the UNHCR and Tzu Chi are working together in an attempt to help resolve the dilemma.

"What do you think you’re doing?” a vendor shouted as a child took off. The short figure soon disappeared into the distance. The vendor, though mad as a hornet, decided not to pursue. He figured the child was probably from a refugee family nearby and was stealing things to fill his empty stomach. There are many children among the Burmese families who have been smuggled into Malaysia. If they are of the Chin ethnicity, who are primarily Christians, they can probably attend schools supported by their churches. But children of the Rohingya ethnicity or other peoples of the Islam faith are not as lucky. They do not have access to schools. Their parents are too busy making a living to attend to them, so they are left to loiter, to beg on the streets, or to steal. The misery facing adult refugees will likely be passed on to their children, unless something positive is done about education. “Education is extremely important to these refugees,” said Yante Ismail, spokesperson for UNHCR Malaysia. “For them, no knowledge results in no power [to strive for a better future].” To prevent poverty from being transmitted from one generation to the next, the UNHCR and Tzu Chi joined forces in September 2007 to promote early childhood education for refugee families. They provide basic skills instruction in reading, writing, and math, as well as character education. They hope their joint effort gives the children a better chance of escaping the hard lives that have bogged down their parents. In October 2007, Tzu Chi volunteers visited refugee communities and selected five of them—Kampung Pandan, Taman Teratai, Taman Tasik Tambahan, Taman Tasik Permai, and Selayang—in which to establish UNHCR Tzu Chi Education Centres. The five centers opened between late 2007 and early 2008. The parents of the refugee students share the cost of the utilities at the schools and also, symbolically, the responsibility for educating their children.

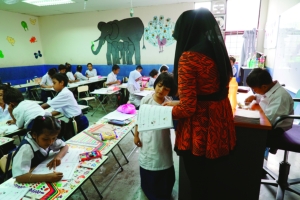

A teacher Three-story row houses stood side-by-side on a major road in Selayang. Just around the corner was a supermarket. Though it was not open yet, many children had gathered outside its front door, chattering away. The boys wore white shirts and long blue pants; the girls had on white smocks, long blue skirts, and white headscarves. They were there not for the supermarket but for the UNHCR Tzu Chi Education Centre next door. Teacher Aisha Kasim, 28, was getting ready for class in the education center. Petite, dark-skinned, and dimpled, she did not look like a mother of two. She was born and raised in a Moslem family in Burma. Because of the religion they practiced, she was ostracized and often bullied in school. Her parents were banned from working. They were forced to pinch their pennies and could only live in run-down rental housing. Aisha’s parents smuggled themselves into Malaysia when she was eight years old. They worked to make money to send home, so she and her two brothers could go to school. The boys stopped after high school, but Aisha kept on going until she got her law degree. Unfortunately, the degree did not improve her prospects. “I couldn’t work, I couldn’t fight for my rights, I simply couldn’t do anything,” she recalled. Aisha’s husband was smuggled into Malaysia in 2006, where he joined her parents. He worked odd jobs and put away money. Two years later, he was able to pay 10,500 ringgits (US$2,710) to human traffickers and get Aisha into Malaysia. Aisha’s mother suffered from high blood pressure, so Aisha often took her to a Tzu Chi free clinic in Malaysia for treatment. She noticed that the doctors there badly needed interpreters, so she volunteered to be one. Her proficiency in English eventually landed her a teaching job at the UNHCR Tzu Chi Education Centre in Selayang. She knows from experience that only education can bring forth opportunities in life. She often tells her students at the center, “You’re very fortunate: This isn’t our country, but you’re in school. You must study hard and try to change your future.”

Rocky roads It is good to see students in class, but their attendance cannot be taken for granted. They may stop attending school for a number of reasons. They may move away because their parents change jobs, or because the law has clamped down on where they live, or even worse because their parents have demanded they start working. To minimize such occurrences, Tzu Chi volunteers keep in close contact with teachers. If necessary, they make home visits to help students iron out issues at home that may prevent them from attending school. Wahida Nur Haq, 9, is in second grade. She walks with her brother, Anand Nur Haq, 12, to school each morning. She always sits quietly in the front row of the classroom. She has attended the education center for four years. At first she knew no English, not even “yes” or “no.” Shy and quiet, she timidly observed the world through her large eyes. Though still reticent to converse, she can read and write English quite well now. She has made several good friends and even answers questions in class. In February 2015, Wahida’s father was on the way to the UNHCR to apply for a replacement refugee card when he was questioned by law enforcement personnel and taken into custody. Teacher Juvita Karmini, 52, informed Tzu Chi volunteers of the situation. They followed the girl home one day when the school let out at noon. Wahida lived in an old apartment building not far behind the school. There were four rooms on each floor. The landlord had divided each room into five or six units for rent to Burmese refugees. Wahida’s family rented one such unit. The wood partitions blocked out the sun, so it was quite dark in their small room. Wahida and her five family members shared their room, small though it was, with another family. The two families split the monthly rent of 500 ringgits (US$130). Rasidah Imran, Wahida’s mother, worked at a factory across from her daughter’s school. She made three ringgits (80 U.S. cents) an hour. She usually worked and worked without taking time off so as to make more money. But on the day the volunteers visited, she rushed across the street overpass to meet them. She broke down and cried the moment she saw the volunteers. She beseeched them to help find out what had happened to her husband. The bail to get him out of detention was four thousand ringgits. If not posted, he would be locked up for four months. Her husband used to work as a laborer in the market, and their combined pay was just about enough to cover their expenses. Though now his income was not coming in, the rent, living expenses, and school expenses remained the same. Not a single expense could be eliminated, so Rasidah had to work extra hard. Despite the difficult situation, Rasidah knew all too well that if her children stopped going to school, they would grow up like her. They’d have no options but to do menial work for little pay. Therefore, she insisted that they stay in school. That would be the best gift that she could give them. Volunteers held Rasidah’s hands with empathy. They were badly calloused due to having labored day and night for so long. The volunteers promised to help the family through this time of hardship. Rasidah embraced them, knowing that she would not be fighting alone on the path ahead. When the home visit was over, Rasidah told Wahida to look after her younger brother, Alias Nur Haq, 6, and she rushed back to work. She did not eat lunch.

The joy and sorrow of teaching Many other students in the school experienced predicaments like those testing Wahida and her family. Knowing that, Juvita kept reminding herself to be patient with the children in her class. “My family was poor too when I was little. We had days when we had no clothes to wear or anything to eat,” Juvita said. “I understand the lowly feeling of theirs.” Despite their hardships, many of her students were actually quite artistic. Juvita encouraged them to paint on the classroom walls. The leisurely swimming whales on one wall was one of their works. What they lacked was not talent, but opportunity. Juvita wanted to leave happy memories in the minds of her students, so she would bring food and presents to her class on holidays or festivals. Knowing that most of them had never celebrated their birthday, she put a birthday calendar in her classroom, and once each month they celebrated the birthdays for that month. “I don’t want the children to focus on what they don’t have. I want them to know that they do in fact have many things,” she said. Juvita used to run a tutoring service. When her husband retired from the police force, she decided to do things that would benefit society, so she interviewed for a teaching position at the UNHCR Tzu Chi Education Centre in Selayang. “During the interview, volunteers showed me around the center,” Juvita said. “They told me that they couldn’t pay me a high salary because of the charitable nature of the job.” Despite that, she accepted the offer without thinking too much about it. Though a veteran teacher, Juvita had a tough time when she first started at the center. She struggled with the language barrier—the children knew no English or Malay, and she did not speak Burmese. She asked students who knew some English to interpret so class could proceed. The situation improved after the UNHCR and Tzu Chi found Burmese teachers to work at the center. The Selayang center had 40 students when it first opened. Juvita and another teacher each led one class. When registration was reopened for a new session, 295 students signed up, far more than the center could accommodate. Volunteers scrambled to find additional classrooms and teachers, and they finally solved the problem. No one was turned away. Juvita has taught at the center for eight years. Given so many refugee families with financial and other difficulties, she has been frustrated many, many times. But nothing has frustrated her more than seeing a child stop coming to school. “Sometimes, out of the blue, a child would just stop coming to school,” she said. “Then a few days later, I might learn that, to avoid the law, the parents had uprooted the family and moved away overnight.” Fortunately, she had had her share of the joy of teaching as well. Many shy children had become more lively. Some whose families were placed in the United States have kept in touch with her. “I’ll teach until I can’t anymore,” she said, adding that teaching is all that she knows how to do and all that she can do for the children.

Graduation Tzu Chi volunteers, like Juvita, are willing to do what they can for the children. They do not require the children to turn in great grades, but they hope that they form good habits and develop positive values. To that end, members of the Tzu Chi Teachers Association and the Tzu Chi Collegiate Association go to the centers twice a month to share Jing Si aphorisms by Master Cheng Yen with the students. Tzu Chi volunteers also organize a sports day for the education centers once a year in conjunction with the UNHCR. Because the students’ usual activities largely confine them to their homes and the centers, volunteers hope the event takes the children out of their daily rut. Volunteers do their best to find a suitable venue and arrange all types of competitions so that the children may have a chance to learn and demonstrate good sportsmanship. On that special day, children don new sportswear, brand-new white sneakers, white socks, and caps provided by volunteers. Then they go at it to get the better of their schoolmates. But, win or lose, they have a great day in the bright sun. Volunteers have made a point of holding a graduation ceremony at the end of each year for those children who have finished six years of school. The children have never experienced a ceremony as solemn as this. After receiving their graduation certificates, the graduates move on to the next phase of their lives with the best wishes of the teachers and volunteers. For many children, graduation means the end of schooling and the beginning of work. Even so, they are now better equipped to fend for themselves than they could if they had not attended the school. The education centers graduated five children in November 2014. UNHCR representative Niaz Ahmad conferred graduation certificates on them. He commended the students’ persistence, which was made all the more admirable by the obstacles they faced and the long odds against them. He also thanked the teachers for their hard work. Then he expressed his hope that the education centers could in the future be extended to cover junior high school, or even senior high school and vocational school education. He knew that only with knowledge and skills could the children be independent in a third country. There is, however, a very long way to go before his vision can become reality. Two of the five education centers—in Kampung Pandan and Taman Teratai—were taken over by local charities and withdrew from the UNHCR and Tzu Chi collaboration pact in September 2009. The three remaining centers have served over three thousand students during the eight years since their inception—a great effort, but still a drop in the bucket compared to all the refugees registered with the UNHCR. Therefore, both the UNHCR and Tzu Chi are still actively promoting their education centers to parents in local communities. |

|