| After Typhoon Haiyan: Rebuilding Lives | ||||||||||||||

| By Li Wei-huang. Translated by Tang Yau-yang. Photos by Huang Xiao-zhe | ||||||||||||||

Typhoon Haiyan, the worst natural disaster in the world in 2013, hit the central Philippines very hard. Tzu Chi has carried out several aid programs since the storm, one of which was building a new village for typhoon victims in Palo, Leyte Province. New Homes Lift SpiritsDuring World War II, as Japanese forces gradually extended their grip on the Philippines, President Roosevelt ordered General Douglas MacArthur to withdraw to the safe allied haven of Australia. When he arrived there, the general made his famous statement, “I came through and I shall return.” Two years later, in 1944, that promise was fulfilled when the general and his troops landed in the municipality of Palo, just south of the Leyte provincial capital of Tacloban, and began their campaign to liberate the Philippines from the Japanese. The MacArthur Landing Memorial National Park, a testimonial to this historic event, has long been a popular tourist destination in Palo. However, on November 8, 2013, Typhoon Haiyan (known in the Philippines as Typhoon Yolanda) laid waste to the region. Even the memorial was damaged. One of the seven statues, that of Brigadier General Carlos Romulo, was knocked off its base. People’s lives were knocked off their bases, too. But whereas the memorial was easier to repair—within 20 days—victims’ lives would take much longer to return to normal.

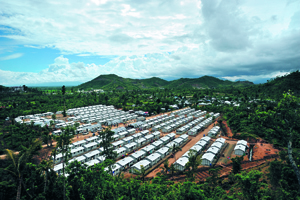

HAIYAN LEFT A PATH OF DESOLATION in which 7,000 people died or went missing and nearly a million homes were damaged. The damage from the disaster remains indelible. Today many people still live in places with only flimsy metal or plastic sheets over their heads. Their walls are nothing more than what they have been able to scavenge and cobble together. But Tzu Chi has been working hard to help victims rebuild their lives since the typhoon. Fifteen months after the disaster, the foundation finished building 255 light-duty housing units on a 3.3-hectare tract in the barangay of San Jose, Palo, just a few kilometers from where MacArthur made his historic return. Fifteen hundred people have moved into the new village. Joel Daga lived in the barangay of Candahug, where the MacArthur memorial is located. After Haiyan, he and his family were put up in one of the bunkhouses that the government had built for victims of the typhoon. These houses, about 110 square feet in size, were built one next to another, separated only by plywood. Bathrooms and kitchens were shared by the residents. Daga shared his small unit with his mother, brother, two sisters and a niece. They had only about 18 square feet per person, just enough for a person to lie flat. The discomfort of the extreme crowdedness was made even less bearable by the sounds of others living in other units. The plywood proved to be a poor sound barrier; every sound, however small, seemed to travel fast and far beyond the walls. “I couldn’t get used to living there,” Daga said of their government-issued quarters. “It was hot and there was no electricity. It was also noisy, and you had no privacy. It was easy to get sick.”

Against such a backdrop, it was understandable how joyful the Daga family must have been when they learned that they would move into one of the 255 units that Tzu Chi would build. Their 285-square-foot unit would have three bedrooms, a living room, kitchen, and bathroom. It would be head and shoulders above the place they had been in, and it would be even better than the house they had lost to Typhoon Haiyan. In addition, of the 255 households slated to move into the new village, about a hundred of them, like Joel Daga’s, used to live in Candahug. Old neighbors would become new neighbors. If all that was not enough, the news got even sweeter: If they wanted, they could help build their houses and get paid for their service. Daga started working in September 2014. He was responsible for pulling steel cables and putting anchors into the ground. The cables and anchors were designed to help hold down and strengthen the units against typhoons. He was paid 250 pesos (US$5.60) a day, just a tad over the local minimum wage. His mother soon joined in and worked too. About two hundred people in all, including future occupants like Daga, other villagers, and even volunteers from other NGOs, worked together to build the houses. Tzu Chi volunteers were on hand to teach them how to do their jobs.

The first hundred households, including Daga’s, moved in on December 17, 2014. One of his sisters is mentally disabled and suffers occasional seizures. She cannot live alone, so her mother shares a room with her. For her safety, Daga and his mother had to lock her in her room when they went on duty to build the rest of the houses. They went back to check on her whenever they had a break on the job. DESPITE A NUMBER OF DIFFICULTIES, the entire village of 255 units was completed in about six months. It has never been easy to acquire public land from the Philippine government for the purpose of building housing, permanent or temporary, for disaster victims. The nation has sold public lands ever since its Spanish colonial era, so public land is not in abundant supply. Alfredo Li (李偉嵩), the CEO of Tzu Chi Philippines, pointed out that the Tacloban and Palo governments had offered five tracts of land for Tzu Chi to build temporary housing for Haiyan victims. However, the foundation accepted only the one in Barangay San Jose, Palo. The other tracts did not satisfy one requirement or another. Teams of Tzu Chi volunteers visited the needy families that were on the government-provided lists to select prospective residents. Some of these families lived in government bunkhouses, and some were still in their own homes which had been damaged and were deemed too dangerous to occupy. During the visitations, volunteers took note of which families contained single parents, elderly, young, disabled, sick, or otherwise disadvantaged people. They gave these households priority as they filled in the list of 255 households.

The Philippines, the 12th most populous nation on the planet, officially became a country of a hundred million people in July 2014. Large families, ones with up to ten children, were quite common among those on the list. Their livelihoods were in serious jeopardy after they had lost everything in the disaster. Even putting food on the table was difficult for many parents. They could really use the relief that their free new homes would provide. The homes Tzu Chi provided came in two sizes: 285 square feet with three bedrooms, like Daga’s, and 215 square feet with two bedrooms. Each unit has a front yard 1.5 meters (4.9 feet) deep and a back yard 2 meters (6.6 feet) deep. Houses are one meter (3.3 feet) apart. Taiwanese volunteer Pan Xin-cheng (潘信成) stationed himself at the construction site when site preparation began, and he stayed there for seven months. “Two or three typhoons hit during the construction period, but our houses came through with flying colors. They’re really sturdy,” he said confidently. BROTHERS KRIS AND GABBY CORPIN, ages 25 and 24 respectively, lived in Barangay Tacuranga, Palo. Besides being siblings, they have several other things in common: Both of them lived in government bunkhouses after Haiyan, both took part in the work relief program, and both moved into new homes at the Tzu Chi village. Each of them has also had a new child. In the village construction program, Kris worked on house frames while Gabby installed doors. They enjoyed the work because they were creating a new village for themselves and getting paid for their work at the same time. Kris was able to save some of the income earned from the work. He wanted to learn to be a hairstylist to make a living.

Kris, his wife, and their child now live in a two-bedroom unit. “It’s bigger than the government bunkhouse that we lived in, and it’s even bigger than the house we lost in the typhoon.” Gabby and his family live next door, so the two brothers can easily look out for each other. Their parents are quite happy about this arrangement. Jason Delector came from the same village as the Cropins. The father of three children used to make a living by climbing up coconut trees to collect sap and fermenting it to make coconut wine, a popular local beverage. But he and many others in the industry lost their livelihoods when Haiyan killed hundreds of millions of coconut trees. To support their families, many of them resorted to odd jobs, such as pedaling pedicabs or peddling goods. When the cash-for-work program started, Delector saw the opportunity and signed up. His job involved using gas chainsaws, something that he had not done before. He needed to learn to mix fuel for the saw, to maintain and keep it in good working condition, and to use it to cut down trees and cut them to size. Those were useful skills, and he was thrilled to be able to learn them under the tutelage of a master technician. This work experience helped him plot a plan for his future: He wanted to be a carpenter. Now he and his family have moved into their new home in the village, and the money he made from the work relief program has allowed him to buy cooking gas—an upgrade from burning wood that he scavenged. He even had some money left over to buy school supplies for his daughter. He is grateful for the program and for their new home. “With this home, our lives have become much more stable.”

PAN XIN-CHENG, the volunteer from Taiwan, observed that 28 teams worked on different aspects of the village construction project at its height. Some teams, including the Corpin brothers, put up house frames and doors. Others, including Joel Daga, pulled steel cables and sank anchors into the ground. Still other teams installed skylights, made and laid cement blocks, dug drainage ditches, or landscaped the area. Among all the jobs, the most noticeable was probably what Jason Delector was involved with, that of wood preparation. His sort of work is not normally seen on a construction site. Delector and his team cut down dead coconut trees, took them back to the building site, and cut them down to different shapes and sizes to be used in the construction. The coconut lumber was used to build things ranging from retaining walls for ditches to dining tables and chairs. Pan said that at first they found that a coconut tree trunk, if purchased from a store, would have cost about 650 pesos (US$14.50). Cutting it down to specifications would have cost an additional 700 pesos (US$15.65). That came to about US$30 a tree, shipping not included. Then they realized that the many dead coconut trees that dotted the slopes around the building site could be used to save them lots of money. Typhoon Haiyan had left them dead but still standing up tall. Tzu Chi obtained permission from landowners to cut down some of those dead trees for use at the building site. Using three gas chainsaws, more than ten participants of the Tzu Chi work relief program felled about a thousand dead coconut trees and hauled them to the work site. Coconut is a versatile plant. Many Tzu Chi village residents used to work in businesses involving this crop in one way or another. For example, Virginia Daga, Joel Daga’s mother, had sold coconuts for ten years. She would pay seven pesos for a coconut and sell it for 15. She could make 240 pesos a day if she sold 30 coconuts. But all that was before Haiyan. The sharply lowered supply of the fruit caused by the typhoon killing large numbers of coconut trees drove up the price so much that she had to shut down her business. Her cost increased to 25 pesos per fruit. Even if she charged just 30 pesos a fruit, lowering her profit from eight pesos to five, she would have few buyers. Furthermore, she had no money to purchase an initial supply to restart her business anyway. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that Haiyan destroyed or damaged 44 million coconut trees in the Philippines. It is not an industry that can recover quickly—it takes the plant six to eight years to mature and bear fruit. Since the coconut-related industry plays an important part in the local agricultural economy, the huge impact can only be imagined. IT TOOK THE EFFORTS of people from different countries to make the project possible. For example, the polypropylene panels used for building the housing units in the Tzu Chi village were made by volunteers in the United States, and the steel frames and parts were made by volunteers in Taiwan. Tzu Chi’s approach to the construction attracted quite a few visitors from other NGOs during the six-month project period. Some of them came to study the design of the homes, some to help erect the units, some to offer goods, and some to help design public spaces, such as the playground. Some of these NGOs even talked with Tzu Chi about possible collaborations in the future. The construction took place during the monsoon season, during which it is common for the weather to be sunny and scorching hot at one moment and raining bucketfuls the next. The construction site, with its exposed dirt, was often very muddy, and the working conditions were very poor. Still, people worked in good spirits. They gathered, sang, and prayed before starting their work each day. The cheerful atmosphere drew the attention of workers from other NGOs. The Tzu Chi Great Love Village in Palo was completed on February 14, 2015, before the government could supply electricity. Taiwanese volunteer Cai Feng-ci (蔡豐賜) provided solar power panels for the families—one panel for two families—so that they could have electricity for lighting. In late afternoons, it seemed that all the children in the village were outdoors, playing and frolicking together. Adults visited one another at their homes and chatted. Having gone through the shared experience of the massive typhoon disaster, it seemed easier for them to bond. Jason Delector told volunteers that his family moved twice after the typhoon, and it wasn’t until they moved into the Tzu Chi village that he finally felt they had settled down. “I feel a happiness that comes from owning my own place.” Volunteers have urged the residents to keep the village tidy and in good order. “Everybody takes it upon themselves to keep the place orderly, clean and safe,” Delector continued. “We all know that it is everyone’s job.” That discipline has helped make the new village a nice place to live. Many of his relatives and friends who did not get to move there were quite envious of him. Joel Daga, another happy resident, is a hard-working young man. While he was still in the cash-for-work program, he sold cups of jelly that he made himself in front of his home at night. He sold the snacks at five pesos apiece, making 2.50 pesos in profit. He said that he was trying to make extra money because he needed to buy medications for his sister and to give their mother spending money. Now that they all have safe homes, village residents have a solid footing on which to build a better life. TZU CHI AID FOR HAIYAN VICTIMS Cash-for-work cleanup programs: 300,000 person-times in Tacloban over a total of 23 days; cleaned up major thoroughfares and helped restore communities to normalcy Emergency cash aid and supplies distributed to almost 70,000 families Provided funding to help repair damaged school buildings and rebuild a church Built more than 200 prefabricated classrooms Completed 255 units in Palo Tzu Chi Great Love Village, and 2,000 more units under construction in Ormoc Funded by donations collected by Tzu Chi in 46 countries dedicated to this disaster |

|