| A Place to Live and Make a Living | ||||||||||||||

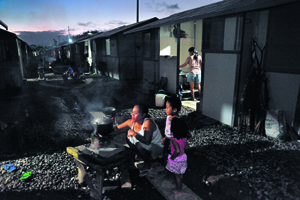

Children in the devastated area that Typhoon Haiyan left behind responded to a survey in which they named the one thing that they wanted more than anything else. Their desire was not for the latest fads or fashion, but the most lasting backbone of an independent family: jobs for their parents. For better or for worse, adversity has hastened these children to maturity beyond their tender age. One recent Sunday morning in the open space at the back of their house in Palo Tzu Chi Great Love Village, Glenda Divino, 35, made a fire with wood scraps to cook breakfast, while just off to one side her oldest daughter, 13, washed a large container of clothes. Though Sunday was traditionally a day of rest, Glenda and her six children did not sleep late. Glenda got up early to do housework, and her children rose early too to help with the chores. The children knew how hard their parents worked to keep the family going. That was true before Typhoon Haiyan hit, it was true afterwards, and it was still true now that they lived in the Tzu Chi village.

Just after the disaster, living in a bunkhouse that the government had built for Haiyan victims was not an enjoyable experience for the family. There were too many people in too little space, and not enough privacy. Now in their new home, they no longer need to share bathrooms and kitchens with other families. Life has definitely improved for them. But Glenda knows that, new home or not, she and her husband still need to work hard just to make ends meet. Their children, young though they may be, somehow seem to know that as well. Through washing clothes for people, Glenda makes 1050 pesos (US$24.00) a week. The eight people in her family eat three kilograms (6.6 pounds) of rice a day. With rice costing 46 pesos a kilogram, the family spends 966 pesos a week. Buying the rice alone just about depletes what Glenda makes from her work. For the last 12 years, her husband has pedaled a pedicab for hire. His income has never been all that great. After deducting 60 pesos a day to rent the tricycle, he has barely enough left over to keep his family going. Even before Haiyan hit, Glenda and her husband had no way of stashing away anything for a rainy day. When that rainy day hit, the typhoon took away their home and most of their belongings. Their lives went from bad to worse. Fortunately, they have a new home in the Tzu Chi village, so at least they have a place to live. Now they and people like them need to find work that can provide them with steady incomes. They also need to learn how to save some of what they earn.

GENERALLY SPEAKING, Filipinos do not save much for their future. If their ordinary way of making a living is disrupted, they often have little savings to fall back on. That’s why, after providing some Haiyan survivors with homes, Tzu Chi volunteers also wanted to help them make a living and manage their income. Volunteer Sally Yunez (施菱菱), from Manila, worked onsite for several months when the Palo village was under construction. She led several women in the kitchen cooking vegetarian meals for people who were building the new village. The women, like the construction workers, were part of the Tzu Chi cash-for-work program. Also like the construction crew, they were learning skills that might help them launch new careers. Yunez hoped that after learning vegetarian cooking skills, the women could make money selling carry-out meals. If they could win steady orders from companies or schools, it would be a good source of income for them. Sound financial planning usually involves raising revenues and containing costs, so Yunez attempted to do both for the villagers. In addition to thinking up ways to help the villagers increase their incomes, she tried to help them save on their expenses. One way was by buying in bulk. A sari-sari store, a sort of convenience store in Filipino communities, plays an important part in the daily life of the locals. A customer can buy “units” of a product instead of whole packages (e.g., one can buy a single cigarette instead of a whole pack). This is convenient for people who do not have enough ready cash on hand to buy the whole package. However, the stores charge higher unit prices for their goods when compared with warehouse stores. The poor actually end up paying more overall for their purchases.

Yunez therefore bought daily goods in large quantities at warehouse stores, divided them into smaller packages, and then sold them to village residents at lower-than-sari-sari prices. She made no profit providing this service to villagers because she just wanted them to save as much money as possible. As a result of Yunez’s efforts, many housewives saw their expenditures go down. A couple of dozen of them even left the money they saved this way with Yunez for safekeeping. Each of them had a personal goal that they wanted to fulfill with their deposits. Most of them wanted to buy motorcycles or tricycles. Both are important means of transportation in the Philippines and can help bring in income for their owners. These women also put aside part of the money they earned from the Tzu Chi work relief program or money left over from housekeeping and gave it to Yunez for safekeeping. Arlene Colinayo was an example. She participated in the work relief program, for which she was paid every other day. The day after each payday, she would deposit 200 pesos with Yunez. “Once the money was in Yunez’s hands, I didn’t want to embarrass myself by making frequent withdrawals,” she said, explaining her strategy for forcing herself to save. She had big plans for the money. Her husband did odd jobs, and he borrowed a tricycle to commute between home and work. She planned to use her savings to buy a bicycle for him. The bike would cost her about 3,200 pesos (US$72), so she participated in the work relief program when it was offered. Now that the program is over, she stays home so she can care for their three young children. However, she plans to find other sources of income and continue to save money. The new bicycle is intended as a birthday gift for her husband. He has no inkling of her plan, so he is in for a big surprise.

Colinayo and her family used to live in a house built of bamboo and straw. After it was destroyed by Typhoon Haiyan, they moved into a government bunkhouse. The house was so small that she and her family could not sleep comfortably. She and her husband had to sleep on their sides to leave room for their children. Now they live in a three-bedroom unit in the new village. Their older daughter got her own room, as did their middle boy. Their youngest sleeps with them. This house is the best home that they have ever owned. TYPHOON HAIYAN severely damaged local businesses that depended on fishing and agriculture, and many people’s livelihoods were impacted. No work means no income. Even young children were aware of this harsh economic reality. When the Save the Children foundation conducted a survey of children in disaster areas, it found that more than anything else they wanted their parents to have jobs. Yunez remembers Ethel, a mother of nine children. After buying coffee and rice from Yunez five times, she managed to save 150 pesos. Her goal was to put away enough to buy a motor scooter, which would cost over 10,000 pesos. Though she still had a long way to go, she worked patiently toward her goal. She hoped to ride the scooter to places that she could not get to on foot so that she could sell more of the snacks she made. She might even do other types of work once she had convenient transportation.

Enhanced mobility may open up work opportunities for some people, such as Ethel, but providing mobility for others can also be a source of income. In October 2014, Tzu Chi provided 200 pedicabs to Haiyan victims who could not afford them in Palo and Tacloban. They can use the pedicabs to make a living. Rolito Barca, a resident of the Tzu Chi village, used to own a hundred coconut trees. He would scale them to collect coconut sap, and use the sap to make coconut wine for sale. Sadly, that livelihood was destroyed when Haiyan wiped out all his trees. Now hope of making a living has returned to Barca, one of the 200 pedicab recipients. He has put the gift to good use. Every morning at six, he takes children from the village to school. These are regular customers that provide him with a steady income. After he drops the children off, he continues to transport adult passengers until the end of his workday at five o’clock. He earns more than 200 pesos a day, enough to make a stable living. It is hard work though. Pedaling passengers during the half-year monsoon season is particularly difficult, as Barca needs to work alternately under the scorching sun and in unceasing downpours. In addition, because many pedicabs rushed into the market after Haiyan, his competition is that much more fierce.

Still, Barca cherishes the opportunity to make a living with his pedicab. He carefully cleans and checks every part of the vehicle before he starts his workday. The daily upkeep is followed by a more thorough tune-up and make-over on Sunday mornings, when he scrubs and polishes the frame, inflates the tires, oils the chains, and pampers his beloved pedicab. “Proper care will make it last longer,” he explained. YUNEZ, PAN XIN-CHENG, and other Tzu Chi volunteers helped out at the village during much of its construction. In addition to giving village residents direct assistance, they also talked with people from like-minded aid organizations about pooling resources and collaborating for the benefit of the villagers. Working together, they have organized workshops on how to make sitting mats, sleeping mats, and other handiwork. If villagers can make them in marketable quality, the volunteers are ready to find organizations or companies to help with commercial distribution.

Villagers and volunteers have also worked together to cultivate a vegetable garden on a slope on one side of the village. Elena used to work in horticulture. When she joined the Tzu Chi work relief program to landscape the village, she showed coworkers how to loosen dirt, put up fences and climbing stands, make compost, and plant seeds or seedlings in the garden. She also snipped off shoots from plants and gave them to residents to plant and grow. If successfully cultivated, the plants could be sold to bring in new income for village residents. A hundred-year-old tree was already on the tract of land that would later be developed into the Palo Tzu Chi village. Though the typhoon had destroyed the old homes of the villagers, it had not killed this tree, which still stood tall and proud. Volunteers decided to leave it alone, leave a sizeable empty space around it, and develop the open space into a playground. Volunteers from Tzu Chi and other NGOs are now working with children to design this space for a playground of their dreams. The space may additionally be used as a co-op marketplace for villagers to sell things that they have grown or made, like snacks, vegetables, fruit, flowers, and handiwork. There are also NGOs working with Tzu Chi on nutrition for children, skills training for women, and personal hygiene for villagers. Space has been reserved for a health center, a skills training workshop, and a day-care center. When children are in good care, their parents can work without a care. The highest level of charity is to help people acquire the ability and means to support themselves: Instead of giving them fish, teach them how to fish. Knowledge and marketable skills are better than riches, and the possession of such things gives the owner more comfort than anything else. Arlene Colinayo helped at the vegetable garden during the work relief program. She later took a class in mat making, and in just a week she became quite good at it. She figures she can make mats in the evening for some extra income if she can find outlets for her handiwork. She confessed that she had been quite bitter after Haiyan had wiped out all her worldly possessions. But living in the new village has exposed her to Tzu Chi ideals and teachings, and has rekindled her power to appreciate and count her blessings. During the cash-for-work program, she worked with a woman who had lost her husband in the typhoon and who was raising three small children alone while pregnant with the fourth. Seeing the tough circumstances of other people made Colinayo further realize how fortunate she was. She was thankful for the fact that her family was well, that her husband was working hard to support their family, and that their children were good and thoughtful. “We’re really fortunate,” she declared. |

|