| A Field of Blessings in a Sink | ||||||||||||||||||

| By Ju Rui-yun Translated by Tang Yau-yang Photos by Chen Hong-dai Used with permission of Rhythms Monthly Magazine | ||||||||||||||||||

The concrete sink, with its outer layer of red and white tiles of various sizes, looks ordinary enough, but it has served a great cause well over the years. Cheng Fu-yuan (程福源) custom-built the sink especially for his wife, Cheng Huang Jin-zhi (程黃金枝), at just the perfect height to suit her in her work: hand-washing second-hand clothes to be given away to the needy. Jin-zhi, 78, is small and thin. Though she looks frail, her back is always straight when she works in front of the sink, her petite arms and hands vigorously scrubbing and rubbing the clothes that she is washing. She is always well groomed, her gray hair pulled up neatly into a bun. Her captivating smile makes people look beyond the wrinkles on her face, wrinkles carved out by many years of hardship. When Jin-zhi is at her sink washing clothes, she is in a world all her own. Others may watch her, keep her company, or wait for her, but nobody may meddle in her business. “My mother-in-law is firm in what she wants to do,” said Qiu Shu-hui (邱淑惠), the wife of Jin-zhi’s second son. “Automatic washing machines don’t cut the mustard for her, so she insists on washing clothes by hand.” After the wash, Jin-zhi hangs the clothes out in the sun until they are thoroughly dry. Afterwards, she carefully and professionally folds each garment, the way a clothing retailer would, before laying them neatly in a box. Filled boxes are then delivered to orphanages or nursing homes.

Cheng Li-na (程麗娜), one of Jin-zhi’s daughters, often arranges transportation for her mother to deliver the clothes. Not knowing the rationale for using boxes, she used to complain to her mother that they took up too much space in the car. She suggested to her mother that she stuff the clean clothes into plastic bags so that the car could hold more clothes on each trip. Jin-zhi explained to her daughter, “I like things to look nice, not all scrunched up.” The daughter gradually came to appreciate why her mother was so insistent: It was out of respect for the recipients that her mother wanted to deliver the clothes to them in great shape, as though they were brand-new. Jin-zhi is also mindful about things that the recipients cannot see. For example, people usually hang their wash up to dry and do not return until late in the afternoon to collect it. Jin-zhi goes beyond that: After she has hung the freshly washed clothes in the sun to dry, she repeatedly returns to check on them and move them to areas which get the most sunlight. She repeats this sun-chasing ritual many times before fondly collecting the clothes for folding and boxing. Because of that level of care, she ends up being in the sun quite a bit. “That’s why Mom gets so tan,” the daughter said. “I really admire her perseverance.” There have been occasions where Jin-zhi’s hands have hurt from continual washing or, in winter, suffered from chilblains from being exposed to cold water for too long. She even developed an eye condition as a result of her being in the sun so much. But in spite of it all, she insists on doing the washing, drying and packing herself. “The pains go away in a couple of days. They don’t bother me. Actually, I often wash clothes all day long without eating or drinking.” Though her family worries that the work might be overtaxing her, she pays them no heed. She just wants to do it. Her mission is front and center in her mind so much that when she talked to her family about how she wanted her affairs handled when she died, she said, “Make sure that the last box of clothes is delivered to people who need them.”

Lifelong devotion Jin-zhi lives in a mountainous area in Keelung where it rains more often than in many other areas in Taiwan. For more than two decades, she has dedicated herself to her mission of washing and giving away used clothes to the needy. Over the years, she has hand-washed over 10,000 garments and given out more than 500 boxes of clothes. She likes to personally put the clothes into the hands of the recipients, so she has traveled to many places in Taiwan to deliver the labor of her love, including New Taipei, Yilan, Taoyuan, Hsinchu, Zhanghua, Kaohsiung, and Pingdong. But of all the places she has delivered clothes to, the Jingren Home for the Disabled in Taoyuan and the Hongde Nursing Home in Yilan have formed the most enduring ties with her. The Hongde Nursing Home, which cares for older people who have nobody else to turn to, started out as an orphanage located in Xindian. Director Chen Xiu-chun (陳秀春) said of Jin-zhi, “She has been donating clothes to us since we were still in our old place in Xindian, and she followed us here to Yilan.” Chen said that Jin-zhi arrives at the home in a private car with her boxes of clothes to donate. Her husband is always with her. In winter she brings them warm clothes, and in summer light clothes. “She always wears a smile,” Chen observed. “She has a kind heart.” At first, Jin-zhi did not even let people at the home know her name or where she lived, so they simply called her “Sister.” Jin-zhi brings many clothes with her on every visit, and they are all washed very clean. “I admire her,” Chen added. “She’s getting on in years, and she’s not all that well-to-do. Still she keeps doing it. You just don’t see people like her every day.” Back when the nursing home was still an orphanage, the excited children would surround the boxes that Jin-zhi had brought with her. They would take the clothes out of the boxes and check them all one by one. “She’s brought us much joy,” Chen concluded. Jin-zhi brings people joy, and she is all smiles in front of them. But in private, she is quite serious about her devotion to giving out clothes. Her mission takes precedence over other things. When she has planned a visit to an orphanage or nursing home, any of her children who is free will have to drive her. If her visit is delayed, she becomes upset. As she got older, she stopped delivering clothes to far-off locations, but she continues to send clothes to those places by courier.

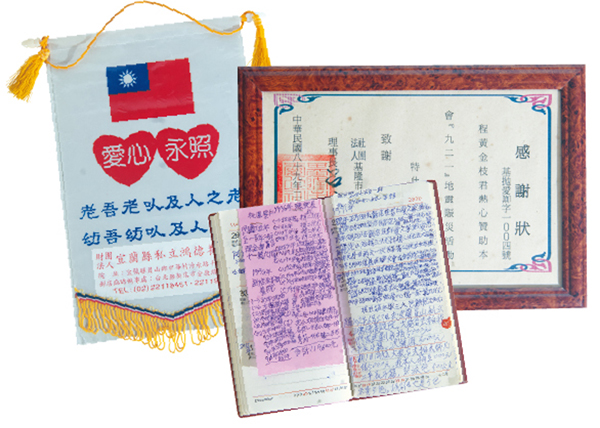

Compassion leads the way How did Jin-zhi’s mission start? How did she become a clothes-giving angel who has warmed many people’s hearts? To answer that question, we have to go back four decades. In October 1973, Jin-zhi, not yet 40, heard on the radio that rain had been leaking into the home of a mentally disabled mother and her four young children, the oldest of whom had just graduated from elementary school. The woman’s husband, an old veteran, had died not long before, leaving the woman to fend for their children alone. Moved with compassion, Jin-zhi set out to visit the family, taking daily necessities such as rice and canned food with her. She had to change buses twice before she reached their home. That marked the beginning of what would become a long list of her benevolent acts. Soon after, she started to donate clothes to the needy. At first, she bought out-of-season garments from stores at reduced prices and gave them to the young and the old. However, she herself was not well off. Buying new clothes to give away was not all that easy on her pockets, especially as some mentally disabled recipients wore out their clothes more quickly. In order to continue her mission, she decided to collect and give out second-hand clothes. She was very mindful of what she selected to donate. She would pick out only clothes that met the needs of her recipients—for example, items that had buttons or zippers on them did not suit recipients who did not have the dexterity to manipulate such fasteners. She and her husband, Fu-yuan, ten years her senior, often scouted neighborhoods and markets during that time for used clothing that would be just right to give away. Later, Jin-zhi joined a charity in Keelung which delivered emergency aid to families in need. One year when she and the group held a winter distribution of daily necessities, the press came to cover the event and learned about her work in giving away garments. When her kind-hearted efforts made the news, phone calls flooded in offering to give her used clothes. She sent her son-in-law, Zhang Zhi-lang (張志郎), to pick up clothes from some donors’ homes but turned down offers from people living too far away. Whatever the source of her donated clothes, she hand-washes the clothes clean and folds them neatly before giving them out. She volunteers for other charity groups too, such as Tzu Chi, where she does recycling.

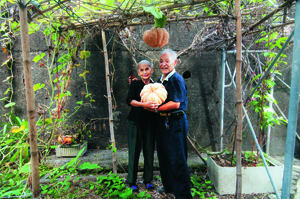

A difficult past Jin-zhi said that she took up charity work for one purpose alone: to love and help others. She had a very hard life growing up, so whenever she thought of people like orphans who were in need of clothes to wear, she wanted to help them. She wanted to spare the children the agony of deprivation, a feeling which she knew only too well. She had a deprived childhood herself. When she was little, a fortuneteller said that she would have to be given up for adoption to survive. At four years of age, she was given away to a mine-worker in Sijiaoting, outside Keelung, who made little money from his job. He lived with a woman and her son. The son often mistreated the young Jin-zhi. The man who adopted her could not really provide for her. She had to walk barefoot to a market in Keelung to scavenge for vegetables for her family, such as it was. The round trip was 13 kilometers (8 miles). She started to cook for the family when she was seven years old. In those early days, she had to make a fire to cook, but lighting a match was a big challenge for her. Often as not, as soon as a matchstick flared up, she would be so scared she’d toss it to the floor. There were other poignant memories. For example, when the son of the woman stole food from the kitchen, he would shamelessly accuse Jin-zhi of the deed, and she would invariably get a good thrashing. One day when she was nine, her adoptive father had a fierce fight with the woman with whom he lived. Jin-zhi took advantage of the opportunity and escaped back to her birth home. She began working as a domestic helper when she was 18, making about two American dollars a month. Illiterate, she enrolled in a night class for four months to learn to write. When I was at her home interviewing her, she showed me a notebook in which she recorded things. The notebook was packed with characters that were quite neat, not an easy feat for someone with little formal schooling. Sometimes she used alternate ways to represent some Chinese characters that were particularly complicated. Take Liugui, a place name, for example. “Liu” means “six” and “gui” means “turtle.” The former character takes just four strokes to write, but the latter requires 16. Instead of writing “gui” out in full, she simply drew a turtle, complete with legs and claws. “Don’t you think that I drew pretty well?” she asked with a mischievous smile. These days, she smiles a lot. So when she took out a portrait of hers created for her when she was 30 years old, I was drawn to the poker face in the drawing. Her face not only lacked a smile, it was devoid of any expression at all. The portrait was made in 1966. She paid 13 U.S. dollars, a huge sum for one who had always been frugal, to have that portrait drawn. Her husband was having an affair at the time. Never much of a breadwinner, he worked extra hard so that he could give money to his mistress, not to his own wife and children. That really hurt Jin-zhi to the core. His affair made her feel so bad that she attempted suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills. If she had succeeded, that portrait would have been displayed at her funeral. Because of her husband’s infidelity, she had to make money to support her five children herself. She sold fruit, vegetables, bread, and even bus tickets to make a living. For ten years, she ate no more than two meals a day. “I used to buy two pounds of noodles for 12 cents,” she said. “Then I’d make noodle soup, split the noodles among my five children, and keep only the liquid for myself. I did the same thing when I cooked mung bean soup; my kids ate the beans, and I only ate the clear soup.” As she recalled that sorry period of her life, she tilted her face up to keep the tears from spilling from her eyes. Despite the pain in the early years of her life, those trying times helped instill compassion in her, making her particularly willing to reach out to the old, weak, sick and needy. A new chapter She eventually divorced her husband and gave him custody of her first, fourth and fifth children, leaving her to raise her second and third children herself. She was also expecting her sixth child at the time. To make money, she worked as a domestic helper, cooking and doing whatever chores she was asked to do. She left her children to the care of her oldest brother’s wife, to whom she paid ten American dollars a month. She contemplated remarrying, although if it were not for finding a home for her children, she would not have considered it at all. Out of more than ten candidates, she picked out Cheng Fu-yuan, who had served in the military for a long time, to be her husband. They had met each other just once, and “it was a done deal in a week,” they said in unison. When asked why she chose Fu-yuan to be her other half, she couldn’t name a specific reason, only mumbling that she had once known another person by the same name and that man had been very nice. Fu-yuan treasures Jin-zhi very much. He said that if it weren’t for her, he would probably be roaming all around now and leading a rootless existence. Their gratitude is mutual. A popular saying goes, “Behind every successful man there is a great woman.” But the reverse is true for Jin-zhi: Her husband has always been her most important support. With his own hands, he made a sink on a raised base for her to wash second-hand clothes. Without this sink, she would have had to squat down to do the job, and that would have been much harder on her joints and muscles. To make it easier for her to hang her wash out to dry, he made a chain out of a discarded electric cable with small loops to keep hangers in place. When she expressed a wish to grow pumpkins and passion fruit, he promptly built an arbor on which the vines could climb. When she needs to collect or donate used clothes, he takes her on his motor scooter. He often video-records the good deeds that she does. All their children agree that their father has been extremely good to their mother, to the extent that he pampers her and grants her every wish. His goodness to her is indisputable. Years ago, when she thought about aborting her sixth child, Fu-yuan convinced her to keep it. Ever since they got married, he has treated all her children like his own. Fu-yuan left the military after they were married. To support his family he worked as an assembly line worker at a match factory, a laborer, a deck hand on a fishing boat, and finally a longshoreman at Keelung Harbor. He has always been a reliable man, and because of that Jin-zhi has been able to help others without worry.

Channeling sorrow into good works Sadly, Jin-zhi’s life didn’t become a smooth ride after she had tied the knot with Fu-yuan. More tragedy was in store for her. Her fifth child, Jian Qiu-fu (簡秋福), and her oldest son, Jian Qiu-fa (簡秋發), died one after another in accidents. Their deaths were cruel, devastating blows to Jin-zhi. Though she gradually was able to come to terms with the harrowing shocks, she still grieves to this day. After the second tragedy, which happened in 2001, Jin-zhi’s daughter Cheng Li-na asked her and Fu-yuan to move in with her so she could better help her mother heal. The mother and daughter grew closer. Over time, they have been more able to focus their energy on helping others around them rather than feel sorry about their loss.

|

|