| Bringing Light to Lives Darkened by AIDS | ||||||||||||||||

| By Zheng Ya-ru Translated by Tang Yau-yang Photos by Hsiao Yiu-hwa | ||||||||||||||||

Prisoners with AIDS are not covered in Singapore’s well-run 3M healthcare systems. In an effort to help this neglected group of people, the Tzu Chi Foundation offers them subsidies for AIDS medications without regard to ethnicity or religion. Foundation volunteers also share Jing Si aphorisms with inmates, hoping to help nourish them spiritually. They do what they can to help brighten the world of these AIDS victims.

Though he offered his hand in a friendly and grateful gesture, I hesitated for a split second, quickly calculating whether to shake his hand or not. In the next instant, I had taken his hand in mine, giving him a firm handshake, and with it my best wishes. But after we parted ways, I could not help checking my hands for signs of open wounds. I could not stop wondering if we had stood close enough that his saliva might have somehow landed in my mouth. I could not even resist examining a mosquito bite on my arm. I was clearly getting carried away, my fear getting the best of me. “Working with AIDS patients is not as unsafe as most people think,” said Karen Lim (林祖慧), a social worker who for the past 15 years has worked at the Tzu Chi Singapore branch. Her composure and steady tone made me feel a bit more secure. It dawned on me that, despite my ostensible acceptance of AIDS patients, I actually wasn’t without doubt and fear when I was in their presence. I still had a ways to go to really accept them, not to mention be a good listener to them and provide care and moral support for them. Fortunately, a group of volunteers in Singapore have been doing just that. Instead of maintaining the general indifference of mainstream society, these volunteers have learned the facts about the disease and are unafraid to go into communities and prisons to accompany people afflicted with this dreaded disease.

The stigma Lily (not her real name), 49, lives in an old flat. She is divorced, an ex-convict, and suffers from bipolar disorder and AIDS. Her life spiraled downwards years ago after her divorce, and she started using drugs as a way to ease her pain. She was committed to prison in 2010. After she was diagnosed with AIDS, she was relegated to an isolation cell and was granted a mere half hour of activity time out of her cell per day. This treatment certainly did nothing to help her live with AIDS. She did not know the facts about the disease, and the bits of misinformation that she had heard through the grapevine scared her half to death. She felt that the medicine she was taking was useless and worried that she would die in jail. She was released from prison in 2011, but she had nowhere to go and nobody to whom she could turn. She stayed away from old friends because she did not want to fall back into her old ways. Instead, she sought help from charities, including Tzu Chi. She worked odd jobs but tired easily because of her illness. She was often depressed. Though she was a Christian, she dared not go to church; every time she went, she felt that Jesus Christ was crying for her. She blamed herself for making her savior cry. She is currently out of a job. The only thing that keeps her going is her twice-a-week visits to her boyfriend in jail, even though he used to beat her after he had taken drugs. His violence put so much pressure on her that she lost ten kilograms (22 pounds) in a short time. Despite that, she waits eagerly for his release. “I told him about my disease, but he said that he didn’t mind and he still wanted to be with me,” Lily said.

Madan (not his real name), 42, also suffers from AIDS. He is of Indian descent. He was in and out of prison twice between 2011 and 2014. He had planned to join his girlfriend after his second release, but when he went home she was nowhere to be found. She had disappeared with all the valuables in his house. Madan was in poor shape financially. He was desperate, having lost his love and his possessions in one fell swoop. It was at this time that he remembered the Tzu Chi volunteers who had visited him in jail. They had told him that he could call them if he ever needed help. He called them and received some emergency assistance that carried him through that hard time.

He now lives with his mother and works in the transportation industry. His vision has deteriorated because of AIDS. When he skips work because he does not feel well, his mother chides him for being lazy. She does not know that her son has AIDS. He was alone when he met with us. His old-fashioned cell phone still showed an intimate photo of him and his ex-girlfriend on its home page. He was mostly quiet while he was with us and did not smile once the whole time.

AIDS subsidy program Since 1985, when the nation identified its first AIDS victim, there have been 6,229 confirmed cases. These patients face many challenges, many of which are not even medical. In addition to dealing with fear and prejudice, they have to manage their finances well to pay for expensive medications. The average bill for drugs runs about 190 Singapore dollars (US$147) a month. Individuals pay more or less depending on the severity of their illness. Some people pay as much as 1,200 dollars (US$928) a month. The financial challenge that accompanies AIDS is often the last straw that breaks patients’ will to fight the disease. When that happens, they simply skip treatments and let the disease destroy their bodies. This could have happened to a Mr. Chen in 1998. His family was overwhelmed by his medical expenses, so much so that his wife sought help from the Tzu Chi Singapore branch. As a result, the foundation issued a check to the Communicable Disease Centre (CDC) of Singapore to help defray Mr. Chen’s drug expenses. A social worker at the CDC noticed that check, which eventually led Tzu Chi to an organized effort to provide care for AIDS patients. “The CDC contacted us in 1999 and asked us to subsidize drug costs for AIDS patients,” recalled Karen Lim, the social worker at Tzu Chi Singapore. Up to that time, the government of Singapore did not subsidize AIDS drugs. “Subsidizing medication for AIDS thus became an area in which our foundation could help out.” When the CDC notified Tzu Chi of individuals needing aid, volunteers began the assistance process. They also made home visits and organized gatherings for patients. Feeling encouraged and cared for, some patients even began participating in Tzu Chi activities or helping with the foundation’s recycling work. Then in 2010, Singapore’s Ministry of Health extended Medifund assistance to cover HIV treatment. Medifund is an endowment fund set up by the Singaporean government to help needy people who are unable to pay for their medical expenses. This was great news for AIDS patients in Singapore, who were then generally able to afford their drug therapy. However, prisoners with AIDS were excluded from this government healthcare coverage. Tzu Chi thus shifted the focus of its AIDS subsidy program from the general public to prisoners. Karen Lim explained that prisoners were largely unable to afford AIDS drugs, and as a result they could die while incarcerated. “They really needed help, so in 2009, at the invitation of Changi Prison, Tzu Chi officially started subsidizing AIDS drugs for inmates.”

Behind bars In the beginning, the assistance that Tzu Chi gave to inmates was confined to drug subsidies. Then, in an effort to meet the spiritual needs of the inmates as well, Lim inquired about the possibility of giving inmates lessons on Jing Si aphorisms by Master Cheng Yen. Prison management allowed volunteers to give such lessons provided that each volunteer first took a training course, passed a test, and was issued a prison volunteer ID. Hong De Qian (洪德謙), a Tzu Chi volunteer who attended the course, said of the prison training program, “They taught us how to interact with inmates, explained to us some crimes and criminal codes, and pointed out prison rules and regulations for us to follow. We had to sign our consent to obey their rules.” Hong is one of ten Tzu Chi volunteers in this prison-visiting program. They average 60 years of age. Most of them are either retired or have jobs that allow flexible work hours. All of them have years of experience visiting people in need. In a typical weekly visit, they show their prison volunteer IDs to enter the main entrance. They sign in in a building separate from the prison, go through other required procedures, and leave their personal effects behind. Only then do they enter a cellblock. After several checkpoints, they finally reach a room where they have two hours with the inmates. It is not a lot of time to spend with the inmates, given the amount of effort to get there, so volunteers strive to make the best use of every minute. Each of them does his or her job. Most of the time, Lo Hsu Hseh Yu (徐雪友), a senior volunteer, and Hong De Qian, an eloquent speaker, do the talking. They mostly discuss Jing Si aphorisms and share related stories. They also show films to supplement their message. They encourage inmates to share their thoughts in an attempt to get to know them better. Most volunteers can speak both Chinese and English, but they choose to speak only Chinese in class. That way, they can ask class participants to translate the lessons into English. Experience tells them that student interpreters often get much more out of the class than they normally would otherwise. “We explain the aphorisms in terms that people can relate to in their everyday lives, and we steer clear of religion so that we can appeal to people of any faith,” said Lim. The residents of Singapore are primarily of Chinese, Malay and Indian descent, and an analysis by the Pew Research Center found Singapore to be the world’s most religiously diverse nation, so messages about universal values are often the most widely accepted. Ooi Hooi Cheng (黃暉卿), 71, has served on the Tzu Chi prison-visiting team for five years. This year he received a Certificate of Appreciation for Pioneer Generation and a Five Year Long Service Award from the Singapore Prison Service. Ooi has made it a point to memorize the names and backgrounds of the prisoners who have taken classes. With such information readily available, he can better console them when they feel down. He often encourages inmates to look at the bright side. “Though you can hardly do much while locked up, you can at least work to enrich your mind and improve your health,” he tells prisoners that he meets.

His fellow volunteer, Chee Meng Yan (朱明仁), also received a Certificate of Appreciation for Pioneer Generation this year. What Chee knew of inmates, before his first prison visit, was formed mostly from what he had seen on TV, which generally portrayed convicts in a stereotypical and unflattering light. “After visiting them in the prison, I find out that they, like us, cry and laugh too.”

Heartfelt embraces Tzu Chi volunteers write case reports for inmates in the foundation’s drug subsidy program, just as they do for needy people or households they regularly visit. In gathering data from inmates for the reports, Hong De Qian was particularly impressed by Gary (not his real name), a 28-year-old prisoner. “He had a very bad attitude when I asked him for information,” Hong recalled. “He felt that he was just getting some medicine—why did he need to answer so many questions? He was very impatient.” But his attitude changed later, as evidenced by the following episode. About a year after Tzu Chi volunteers had started the aphorism classes, Gary told Hong during a class that his mother had recently visited him and told him that his four-year-old daughter had died of illness. Though shocked and sad, Gary said to her, “Mom, I love you.” His mother was at first surprised by his unusual expression of feelings. Then tears streamed down her face. The two of them embraced and cried. Gary told Hong that he had felt much better after that big cry. Prompted by Gary’s sharing, Hong asked the class how long it had been since they had last expressed their love to their families. His question unexpectedly caused several inmates who had usually appeared strong to cry. The effect of this episode remained with those present. Many inmates subsequently opened up and expressed their care and regrets to their own families when their families visited them. Hong said that almost every one of the inmates has a copy of Jing Si aphorisms compiled by Tzu Chi volunteers. “Many have committed the sentences to memory, and some of them can even tell you where sentences such as ‘We mustn’t delay in doing good deeds and practicing filial piety’ and ‘Getting angry is temporary insanity’ appear in their copy.” But what moved Hong the most was not their capacity to recite but their courage to put these wise words into action. Volunteers never ask their subjects on their prison visits why they are in prison or how they got infected. They talk to them only about the present and the future, not the past. They also do not treat prisoners like contagious patients. Instead, they hug and shake hands with them quite normally. “We are aware of the need to protect ourselves,” said Chee. “We don’t have body contact with them if we have open wounds. In those situations, we tell them so frankly and ask them to understand.” Chee believes that being frank and open is the best way to win the acceptance of inmates. The volunteers have worked with the inmates for a long time and have won their trust and friendship. Inmates asked after and sent their regards to volunteers Lo Hsu Hseh Yu when her father passed away, when Chee Meng Yan had an operation, and when Hong De Qian hurt his foot.

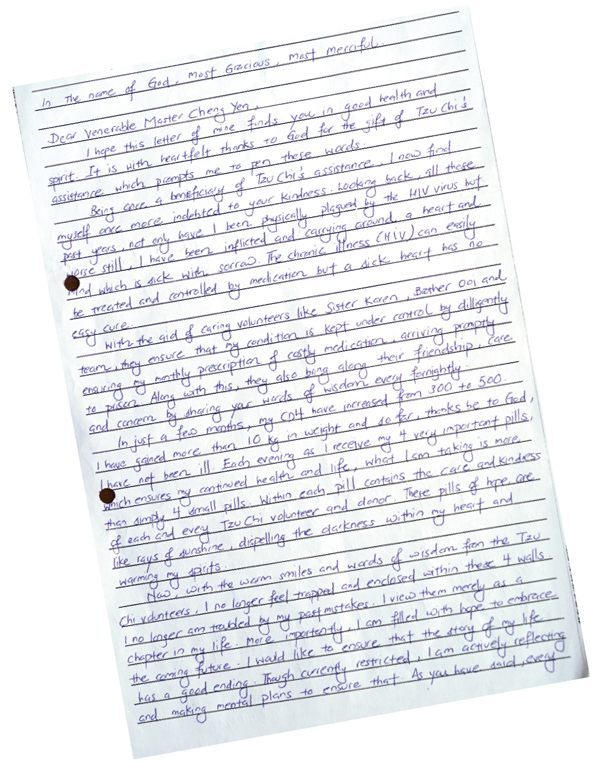

The inmates also show their appreciation in other ways. They are allowed two outbound letters a month. Some inmates used both of theirs to write to volunteers. Some of them wrote a joint letter to volunteers saying, among other things, “We’re but a group of people who have done wrong for which we’re serving time, but you come to care for us all the same. Thank you for helping us without regard to our religions. That really warms our hearts.”

Long road back to society Volunteers currently teach aphorism classes to male inmates at Cluster A and Cluster B and to women at the Changi Women’s Prison, which are all within the Changi Prison Complex. Close to a hundred inmates attend these classes; 56 of them are in Tzu Chi’s AIDS drug subsidy program. After each class, Lim informs correction officers on what transpired in the class. “I’ve also invited the officers to watch a sutra adaptation staged by Tzu Chi volunteers, and I’ve talked to them about how to do recycling in the prison,” Lim said. The favorable impression that Tzu Chi volunteers have made on prison management can be shown in the following two examples. Prison rules do not allow visitors to bring in their own containers for drinking water. Therefore, volunteers used to have to use prison-supplied single-use cups. After being exposed to the volunteers’ conservation messages, prison officials placed ceramic mugs—made by inmates—in Clusters A and B for Tzu Chi volunteers to use. Officials also invited Lim to give a lesson on AIDS prevention at the end of each month for inmates being released from incarceration into society. Tzu Chi offers emergency assistance to ex-cons to help ease their reintegration into society. Volunteers also encourage them to repair their relationships with their families. In addition, Lim and her fellow volunteers do presentations or lead activities at halfway houses. “We hope to help ex-prisoners learn more about Tzu Chi, and we hope that they will seek us out when they need help in the future,” Lim said. Some of them, like Lily and Madan, have sought help from the foundation. Lim firmly believes that on-going follow-ups with ex-convicts are essential to helping them in a substantive manner. “If we don’t follow up, we’ll never know what their real problems are,” she asserted. Ivan, 38, was released not long ago. Perhaps because of the considerable difficulties of returning to society, he had thought about giving up on himself. But the Jing Si aphorism classes that he had attended in prison helped him kindle positive thoughts towards the future. He has since found work and returned to a normal life. Ivan was not entirely forthcoming in the process of looking for work. He told his current employer that he had AIDS but said nothing about his imprisonment. “My boss is really nice to me. He knows that I have a weak immune system due to AIDS,” Ivan said. “One time I was out sick for three months, and he still let me keep my job.” There is no denying that difficulties abound on the road back to normalcy for all ex-convicts, and their situations only get tougher when they have AIDS. When they encounter prejudices and all those other things that are stacked against them, they get frustrated. Who would not feel the same? At times like those, Tzu Chi volunteers become a safety net for them. They listen to what is on their minds, give them support, and take slow steps with them as they attempt to reestablish themselves in mainstream society. That reestablishment process is long, and, as if the stigmas and prejudices were not enough, ex-cons face the real danger of relapsing into their old ways by re-associating with their previous bad influences. “When I met my old buddies after my release, they asked me to peddle drugs for them again,” Lily remarked. “But I said ‘no way.’ I don’t want to touch drugs ever again. One bad thing about drugs is that they lead you to contract diseases.” Having already had a disastrous experience with drugs, she said that she had no more time to waste on them. “All I want is to live a normal life.” The image of my hesitant handshake with a friendly AIDS sufferer at the beginning of this article suddenly flashed back in my mind. Anybody could have that kind of hesitation, and that is proof enough that there is an invisible wall between those of us in the mainstream, and people on the fringes. They want very much to climb over that tall wall to reach us, to become us. Let us be among the first to remove a brick from that wall. Let us be the ones to help bring the wall down. |

|