| Cells of Life—Two Decades of Saving Lives | ||||||||||||||||||

| By Li Wei-huang Compiled and translated by Tang Yau-yang | ||||||||||||||||||

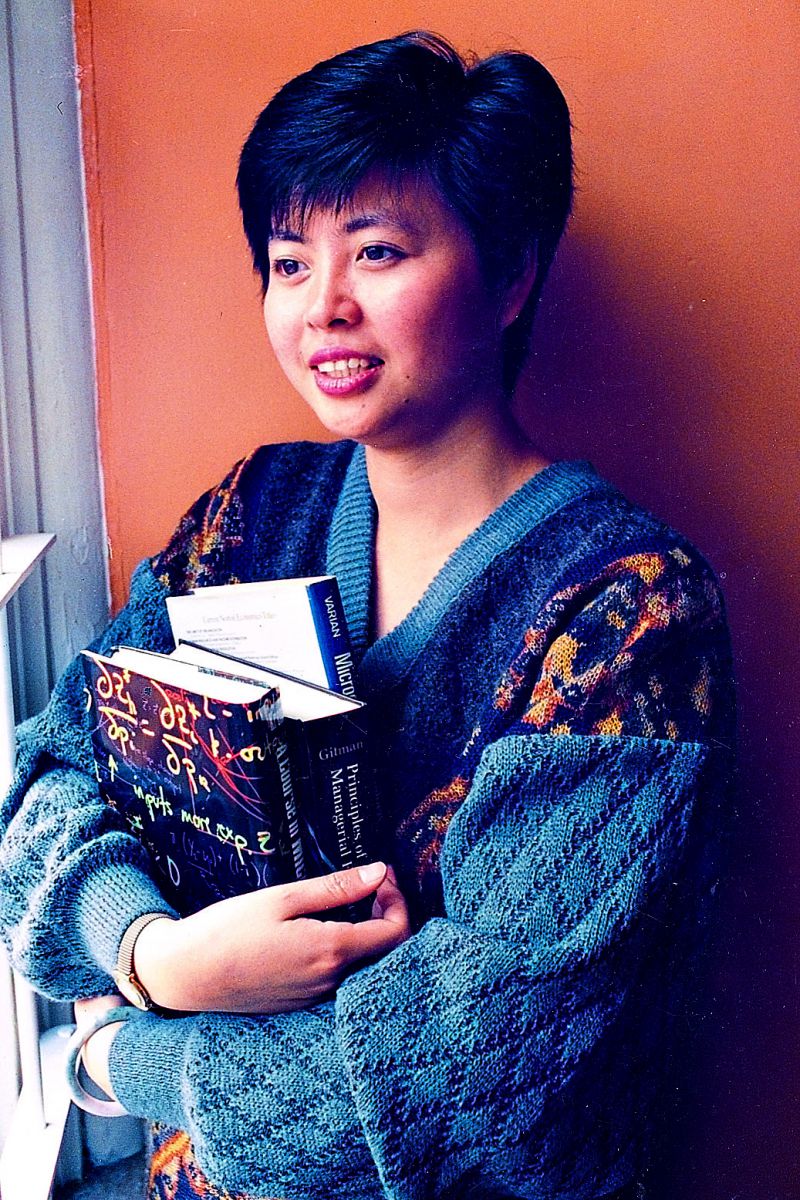

The Buddhist Tzu Chi Stem Cell Center has been a bridge between volunteer donors and blood cancer patients since its founding. Its efforts over the years have helped raise awareness about stem cell donation, and in 2012 alone it led 354 Taiwanese to donate their stem cells. In the 20 years of its existence, the center has distributed stem cells to nearly 3,300 recipients in 28 countries. Blood stem cell transplantation has become an effective treatment for certain kinds of blood cancers, and it is even useful in treating other diseases, from immunodeficiency to sickle-cell anemia. In earlier days, the stem cells were provided entirely by bone marrow transplants. However, peripheral blood stem cells are now the most common source, collected through a process called apheresis, which for the donor is similar to a regular blood donation. Before 1993, Taiwanese law used to prohibit stem cell donations to unrelated recipients. This meant that patients suffering from blood cancer were limited to seeking compatible stem cell donors—those with matching human leukocyte antigen (HLA)—from their relatives only. This restriction greatly reduced the chance they would ever receive the lifesaving treatment. There were parents who, out of desperation, conceived and became pregnant for the sole purpose of getting a chance, however small, that their newborn baby might be a stem cell donor for their sick child. In 1992, Wen Wen-ling (溫文玲) was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia. At that time, the 29-year-old Taiwanese student was studying at the University of Iowa in the United States. Doctors concluded an autologous marrow transplant (one from her own body) was not advisable; unfortunately, the HLA of her parents and siblings did not match hers. Because people from a common ethnic background offer the best hope of a match, teachers and students at her university and Tzu Chi volunteers in the United States held bone marrow drives among people of Chinese descent in the hope that they could locate a suitable donor for her. Unfortunately, those drives and even the sizable bone marrow registry in the United States did not yield a suitable donor for Wen. The young woman thought of her own fellow countrymen, who might be facing the same predicament. If strangers and friends in Iowa could do so much to help her, she figured she ought, and indeed had the responsibility, to do something for blood cancer patients in Taiwan. She packed up and returned to Taiwan in September 1992, six months after her cancer diagnosis. She felt that it was incumbent upon her to help change the restrictive laws in Taiwan surrounding stem cell donations so that blood cancer sufferers in her native land would have better chances of obtaining transplants. The probability of a match for these patients could only be increased if the pool of potential donors was enlarged to include unrelated people. For many, such donations were their best shot at surviving their disease. Together with Dr. Chen Yao-chang (陳耀昌) of National Taiwan University Hospital, Wen lobbied the Department of Health to change the law. Their efforts and those of many others finally prompted the department to submit a bill that would abolish the restrictions. The bill sailed through the three reads needed for legislative passage in just one day, all on May 18, 1993. On May 21, 1993, then–President Lee Teng-hui announced the new law, which opened stem cell donations to unrelated parties. Less than three months later, on August 13, 1993, 1,094 milliliters (37 fluid ounces) of bone marrow were harvested from a donor at Queen Mary Hospital in Hong Kong. As soon as the marrow was processed, the lifesaving liquid was flown to Taipei for transplant into a Mr. Xie at Veterans General Hospital. Although the donor was in Hong Kong, that procedure was the first marrow transplant between unrelated parties carried out in Taiwan. Though the legal barriers had been lifted, another obstacle, no less daunting, remained: the establishment of a meaningful marrow donor registry. Based on his clinical experience, Dr. Chen Yao-chang figured that a registry of 20,000 potential donors in Taiwan could yield matches for 20 percent of the patients requesting donations. A 100,000-member registry could raise the odds to 50 percent. Whether 20,000, 100,000, or even more, such a large registry would require huge sums of money and a large amount of effort to operate. Dr. Chen and others in the medical field in Taiwan turned their eyes to Tzu Chi—a private charity foundation that had earned the trust of the public—for the establishment and operation of such an organization.

A bone marrow registry in Taiwan The first marrow transplant in the world took place in 1958. The donor and recipient were identical twins. There have been more than a million cases of completed stem cell transplants worldwide since that time, including those involving unrelated donors. More than 50,000 transplants now take place each year around the world. Many of these transplants have been made possible because of the existence of marrow registries in many countries which support each other across national boundaries. It is impossible for any one registry, even the largest and the best run, to satisfy all the donation requests it may receive. The reason is a matter of ethnicity—no registry can possibly possess enough varieties of donor ethnicities to satisfy the requests from all ethnic groups. When Wen Wen-ling, the University of Iowa student, was struck with her blood disease, there were no large-scale marrow registries anywhere that listed primarily registrants of Chinese descent. Wen and Dr. Chen visited Master Cheng Yen and expressed their hope that Tzu Chi could establish a marrow registry in Taiwan. They persuaded the Master to consider the possibility. However, there were also people who tried to dissuade the Master. In addition to pointing out the exorbitant cost of the proposed undertaking, they suggested a more hypothetical yet possibly more frightening scenario. Just before the scheduled transplant, the recipient is treated with high-dose chemotherapy, radiation, or both, to kill any cancer cells as well as all the healthy bone marrow in his or her body—to wipe the slate clean so that the transplanted healthy marrow can produce new blood cells unimpeded. However, this leaves the patient with no immune system to fight infections or diseases until the new blood is produced. If the donor were to back out at that critical time, the patient would have to be confined in a sterile room until some other donor was found. There would be no going back. Notwithstanding these attempts to dissuade her, once Master Cheng Yen had obtained the opinion of medical experts and understood that a marrow donation would not harm the donor (a common misconception), she decided to go for it. The Tzu Chi Bone Marrow Registry was officially founded in October 1993. Just prior to that, in August 1993, National Taiwan University Hospital had held a marrow registry drive. It was the first such drive in Taiwan after the new law allowed such activity. That day, more than 2,000 potential new donors gave blood specimens to be tested for HLA compatibility. The enthusiastic response surprised even Dr. Chen Yao-chang. On behalf of his hospital, Chen turned over the data on these specimens to the Tzu Chi Bone Marrow Registry, as well as 400,000 U.S. dollars that the hospital had raised for marrow transplants. Though Wen Wen-ling died soon after the establishment of the Tzu Chi registry, the organization that she helped bring into existence would go on to save the lives of many blood cancer patients. The first marrow transplantation between two unrelated Taiwanese occurred in May 1994 when college student Ye Mei-jing (葉美菁) donated to Wei Zhi-xiang (魏志祥), a 17-year-old young man.

The registry and its volunteers A key reason for the Master to choose to establish the registry, even though she was fully aware of the daunting tasks ahead, was the belief that life is priceless. The road to a successful stem cell transplant is indeed strewn with roadblocks. First, the chance of an HLA match is extremely low, occurring once in 10,000 or even 100,000 tries. Second, even with a match and an ensuing transplant, the risk of complications such as rejection is always present. Despite the long odds, the Master believed that “If we do it, the patient has at least a 1-in-100,000 chance. We mustn’t give up simply because it’s difficult. We should sincerely do whatever we can.” She was confident that people in Taiwan would come through in support of the registry. Most bone marrow registries around the world are supported by government funds, and for good reason. For each blood specimen collected from a potential donor at a registry drive, Tzu Chi pays 10,000 Taiwanese dollars (US$333) to have it processed for HLA typing (to match the donor with a compatible recipient) and have the information saved in its database. That is but one of many costs, tangible and intangible, necessary to maintain a marrow donor registry. With the addition of more services and technologies, the Tzu Chi Bone Marrow Registry was renamed the Buddhist Tzu Chi Stem Cell Center on April 30, 2002. Currently, the center maintains data on 375,000 donors and 12,000 umbilical cord blood units. The cost for obtaining the data on the 375,000 blood samples alone would be US$125 million in today’s dollars. Yet, for the past two decades, the center has operated primarily with donated funds from the public. How is this possible? At Tzu Chi, volunteers handle many aspects of stem cell donations—a factor that Yeh Chin-chuan (葉金川), a former director of the Stem Cell Center, pointed out as having significantly lowered operating costs. If it weren’t for these volunteers, Tzu Chi would be hard pressed to keep the center running. “No other medical centers or social welfare groups in Taiwan have the ability to take on the job of establishing a bone marrow registry,” said Dr. Wang Cheng-jun (王成俊), the attending physician for the first recipient of marrow donated through the Tzu Chi registry. “You can’t find this brand of care for marrow recipients and donors anywhere else,” he added, referring to the practice of having two teams of Tzu Chi volunteers separately but simultaneously caring for the two families on either end of the donation process, through all stages of the transplant. Wang had observed how Tzu Chi volunteers worked in marrow transplant cases. They were involved with much more than promoting the concept of marrow donations. After a match was identified, they also contacted the donor, explained the process and answered questions, and accompanied the parties involved in the process from beginning to end. They even continued to work with them after the transplant. “Many donors have hesitated and changed their minds,” Wang said. “But, [persuaded by Tzu Chi volunteers,] they’ve changed their minds back again and actually donated. The efforts of the Tzu Chi volunteers have greatly elevated the success rates of marrow donations in Taiwan.” Wang has also seen these same volunteers rudely and unfairly treated and denounced by distressed family members. Volunteers silently and uncomplainingly take the brunt of the bad words and accusations, however untrue they really are, and continue with their job of making a transplant a reality. Yang Guo-liang (楊國梁), the current director of the Tzu Chi Stem Cell Center, also lauded the volunteers. He commented that even though they are not medical personnel, they have been trained and certified for the specialized tasks they perform. Yang believes that they are on the frontline of saving blood cancer patients, and that they are the unsung heroes in any stem cell transplant.

Hurdles abound Identifying a suitable donor for a patient on the registry computer is certainly great news, but it can also be the beginning of a protracted process to track down the donor. Several years or even more than a decade may have passed since the donor gave his or her blood for HLA typing. When hopeful volunteers try to contact the donor, they may be calling a disconnected number or knocking on a door where the donor no longer lives. Sometimes the donor has moved without leaving a forwarding address. Some have even moved several times, making it all the more difficult to locate them. It is a good thing volunteers do not easily give up. Despite their best efforts, however, it is always possible that the volunteers simply cannot find the donor. All the trails may have turned cold. Even when the volunteers find the donor, other hurdles may still be in store. Donors are often surprised when finally notified of a match. So much time may have passed that they may have totally forgotten about their decision to donate, or they may have changed their minds. Or their life circumstances may have changed substantially: Some donors may have gone abroad to study, others may be taking medication or have contracted diseases that disqualify them, and still others may be pregnant and cannot donate until later, which might be too late for the recipient. Most of these scenarios make it impossible for a donation to be carried out—a most disheartening situation after hope has been raised by the HLA match. As if all the above were not difficult enough, the ultimate and most daunting of all obstacles is often the objections of the donor’s family. Their objections stem not from a lack of love or concern for the patient, but from fear that the donation might harm their loved one—fear that is based not on scientific facts but on social misconceptions. “If you dare to donate, then don’t bother talking to me about marrying my daughter,” a father threatened his presumptive future son-in-law. In another instance, a mother told her daughter, “If you donate, I will disown you and sever all ties with you as mother and daughter.” The mother had mistaken a bone marrow donation for a spinal tap—a risky procedure in her mind. No wonder she would stop at nothing to keep her daughter from donating—to protect her, she thought. The stigma against marrow donation, however unfounded, has deep roots. A young man confided that he had wavered in his resolve to donate in the face of the vehement objections of his family and friends. He had questioned whether or not it would be worth the hassle to argue so fiercely with his parents over something that concerned a total stranger. But then he asked himself, “What if the waiting patient was my own relative?” In the end, he held his ground and donated as scheduled. One donor, Mr. Zhang, donated some time ago, but he still hasn’t told his mother or father-in-law about it. “I just don’t want them to have any excuse to blame the marrow donation if I should get sick in the future,” he explained. It’s worth noting that it has been more than ten years since his donation. It was most thoughtful of him to donate to help a patient in dire straits, and he has also been most considerate to keep it under wraps to prevent any risk of blemishing the Stem Cell Center, the labor of love of so many caring people over such a long time. Chen Nai-yu (陳乃裕), the executive director of the center’s volunteer team, said that in the past, when the concept of stem cell donation was even more widely and wildly misunderstood, many people donated without letting their families know about it. They went through all the procedures alone, and there were cases when those donors could have used the help and care of their families. In 1994, Tzu Chi established the volunteer team to, among other things, accompany and support donors. The team expanded its scope in 2002 to offer financial and other support to recipients and their families. “Even just one naysayer in the family can be enough to sway a potential donor away from a donation,” Chen said. He noted that volunteers would step up their efforts to present correct information and dispel misconceptions. Any obstacle along the way can be a showstopper. That is why every bone marrow transplant is a small miracle, a real blessing. There can also be bright spots along the way. Donor Chen Di-li (陳帝利) was in the United Kingdom studying for her doctorate when she received notification of a match. Her family fully supported her decision to follow through with the donation. She made three trips back to Taiwan: one trip for a second blood test to ascertain that she was indeed a suitable donor, another trip for a thorough physical examination, and the third trip for the donation in September 2011. She spent a hundred hours traveling, and more than US$7,000 of her own money on plane tickets.

Making a difference The chance of two unrelated persons having matching HLA is so minuscule—from one in tens of thousands to one in one hundred thousand—that volunteers are determined to do everything possible to take an identified match all the way through to a successful transplant. Liu Jia-xun (劉佳勳) got to know a great number of people during his career as a police officer. Now retired, he is a volunteer for the Tzu Chi Stem Cell Center. His wealth of acquaintances has come in handy, helping him track down many potential donors who have been matched with patients, but who have moved from their address on record at the center. He does whatever he can to find such donors. If his subject is the only match in the registry, he becomes especially determined to track that person down. “As long as he or she is living, I’ll do my utmost to find that person, here or abroad,” Liu said resolutely. Liu and other volunteers once went to a donor’s home in Pingdong, southern Taiwan. The donor’s father, who was himself waiting for a suitable kidney donor, steadfastly refused to let the volunteers in. He shouted through the shut door, “You want my son to save another person, but who’s going to save me?” Liu stepped forward and replied, “Think about it. Suppose a suitable kidney donor is finally identified for you, but he doesn’t want to donate….” That bit of reasoning did the trick, and the father agreed to let his son donate his stem cells. Liu had spoken in a language that the father understood and could identify with. Liu had done his homework, and he knew that the father was on dialysis while waiting for a kidney donor. Since his retirement, Liu has been active in spreading the word on stem cell donation at many colleges, police stations, firehouses, and even an Air Force base in his area. He strongly believes that it is something worth promoting. Like Liu, Song Xiu-rui (宋秀瑞) actively volunteers for the Stem Cell Center. She has also had her share of difficulties with the families of some donors. Once she went to visit a donor, and she even managed to get inside his home. But the family ignored her, leaving her alone in a corner of the house. She waited patiently until the TV commercials came on before she talked to them, explaining that a stem cell donation can save a life without harming the donor. Despite the chilly response of the family, she worked diligently and patiently for the cause. In over a decade, Song has accompanied more than 300 stem cell recipients. She has been in and out of hospitals an untold number of times, even on Chinese New Year, the most important family holiday in Chinese society. She clearly knows the suffering of her patients and their families. This knowledge has helped her remain committed to helping them. Thinking of them, she tells herself, “I mustn’t give up, no matter what setbacks I may be experiencing.” Cases of refusal to donate happen not just in Taiwan but all over the world. From the standpoint of helping blood cancer patients, it would be fundamentally sounder to expand the size of the donor registry by raising the willingness of more people to donate. The more potential donors there are in the pool, the more chance a patient can find a match, and the higher the odds of an actual donation and transplant. That is why Tzu Chi volunteers have conducted stem cell drives throughout Taiwan over the last 20 years. Now they do about 120 drives a year.

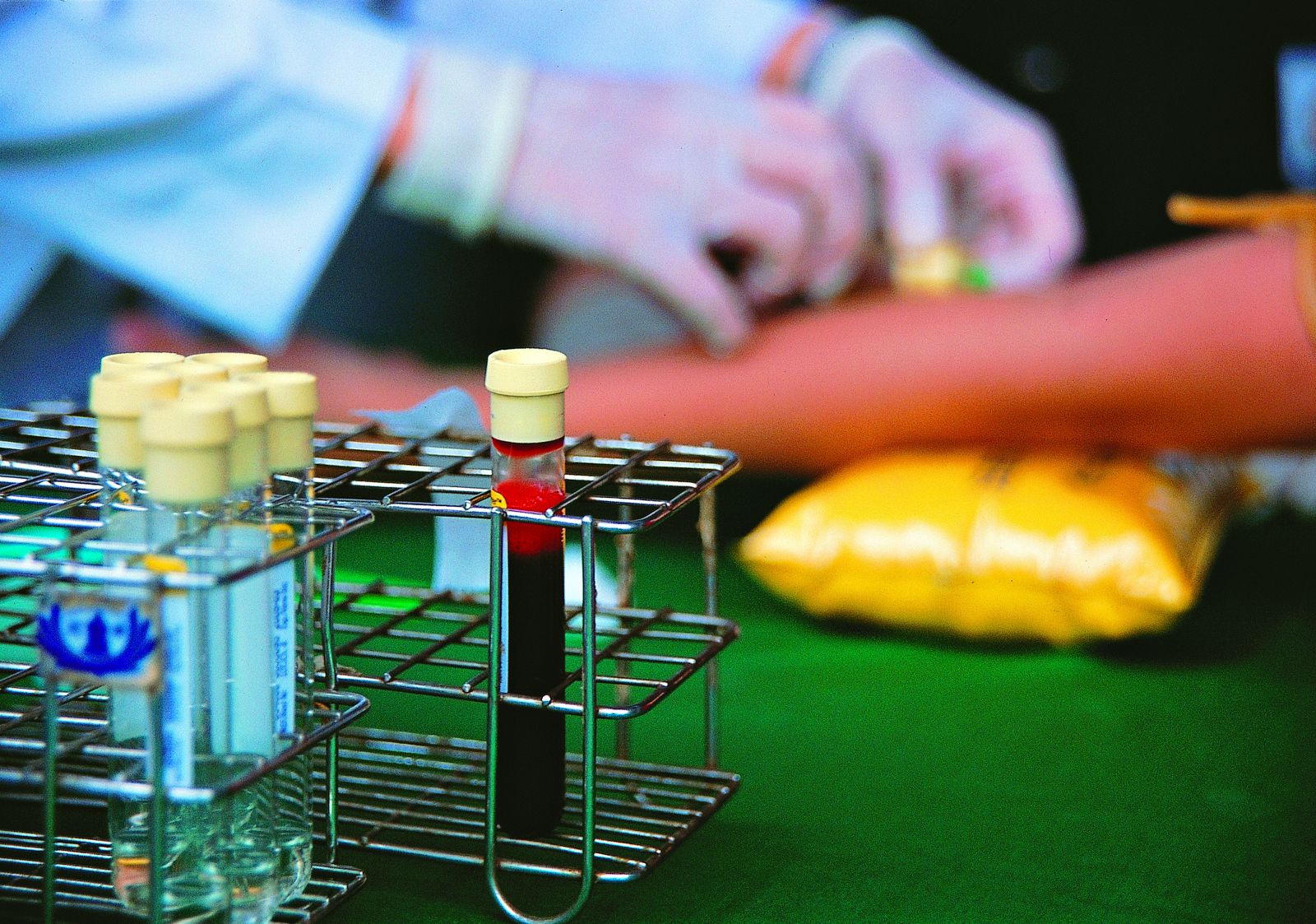

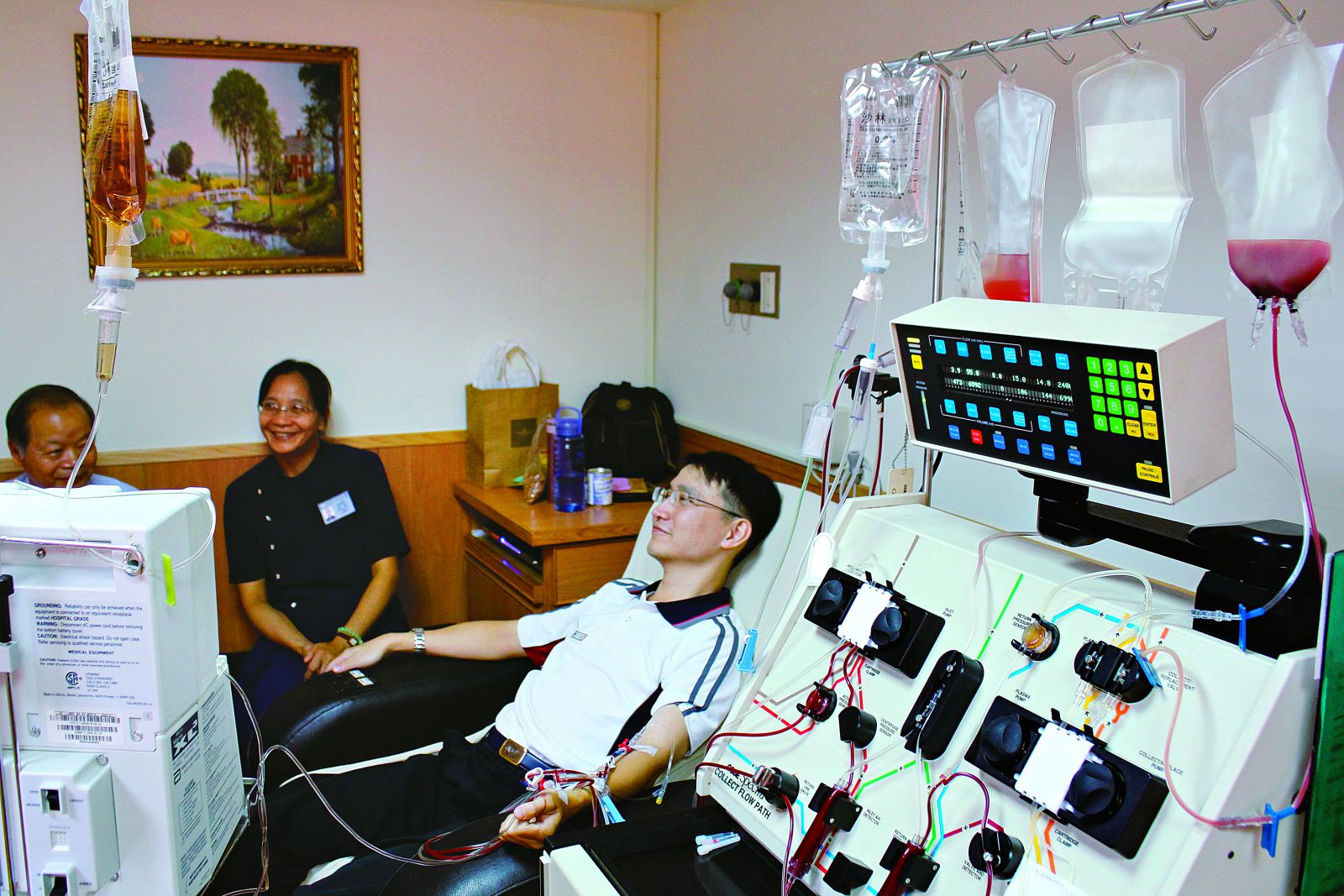

Sources of HSCs For a stem cell transplant donation, about five percent of a donor’s hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are taken. These types of stem cells were traditionally collected from the marrow in a large bone in the donor, such as the pelvis. A large needle was inserted into the bone and the HSCs were withdrawn. The donor was under general anesthesia during the harvest, and the donor’s body would automatically replenish the lost cells in about ten days’ time. Donors were willing to undergo all this in order to save lives. Mr. Zhang, of Zhanghua, central Taiwan, donated his bone marrow years ago. He touched his hip where two needles had been inserted to withdraw marrow, and he said, “I don’t understand why on earth people, after being HLA matched, could get cold feet or just flat change their minds.” Zhang commented that it is much easier to donate stem cells today than when he did it. For example, HSCs can also be obtained from umbilical cord blood when a mother donates her infant’s umbilical cord and placenta. This blood typically has a higher concentration of HSCs than adult blood. However, the small amount of blood obtained from this source makes it better suited for a transplant into a small child than into an adult. These days, most HSCs are harvested from peripheral blood, a procedure that is much simpler, very similar to donating blood. Before the actual procedure, called apheresis, the donor receives daily injections of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, which mobilizes stem cells from the donor’s bone marrow into the peripheral circulation. Then, during apheresis, the donor’s blood is taken out through a needle in one arm and passed through a machine that extracts the stem cells. The rest of the blood is returned to the donor.

The report card During its first two decades of effort, the Tzu Chi Stem Cell Center has signed up 375,000 donors for HLA typing and completed nearly 3,300 stem cell donations. One third of those donations have been to people in Taiwan, one third to China, and one third to patients in the rest of the world. All told, blood cancer patients in 28 nations have benefited. An average of 440 requests for HLA matching come into the center each month, of which 400 originate outside Taiwan. In 2012, 354 Taiwanese donated their stem cells, almost one a day—not bad for an island of 23 million people. Many donors alter their daily routines in preparation for the donation. Some enrich their diet to put on weight, some suspend their weight-loss diet, and still others force themselves to exercise to get healthier. While individual adjustments may vary, they all try to get in shape so that the stem cells they donate are in tip-top shape. They want to give their very best.

● Wen Wen-ling helped change the law to allow stem cell donations between unrelated parties in Taiwan, but she herself never directly benefited from the Tzu Chi registry. She did find a suitable donor from the Hong Kong Bone Marrow Donor Registry, and her transplant was performed in the United States. However, she died from pneumonia in February 1994. To commemorate her courage and influence, the University of Iowa had its flag flown at half-mast. A headline in a local paper read, “Woman changes law of her land.” Wen’s younger sister, Wen Wen-hua (溫文華), who had accompanied Wen in her search for a marrow donor, said, “Though my sister is gone, we have no regrets.” Dr. Chen Yao-chang, who worked with Wen Wen-ling in her efforts, said, “I feel that we really did the right thing [to help bring the Tzu Chi Bone Marrow Registry into existence].” Dr. Wang Cheng-jun, the attending physician for Wei Zhi-xiang, the first recipient of stem cells from an unrelated donor in Taiwan, is now a private practitioner in northern Taiwan. He continues to be involved with stem cell donations. He administers daily injections of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor for donors of peripheral blood stem cells to get them ready for donations, and he follows up on their conditions afterwards. College student Ye Mei-jing, the first unrelated donor in Taiwan, gave her stem cells without her mother’s knowledge in May 1994. When the mother later found out, she became concerned about Mei-jing’s health and capacity to be a wife and a mother. Now, almost 20 years later, Mei-jing is a healthy wife and mother, and she works as a prosecutor. She has thoroughly proved her mother wrong in her well-meaning but misguided concerns. Wei Zhi-xiang, the recipient of her stem cells, did not survive because, having been weakened by prior chemotherapy, he was not in the best condition when he received the cells. Mei-jing had this to say: “I can’t decide the outcome of many things in life, but what matters more is the process—something that I did make an effort to contribute to.” She wants to tell everyone, “Never pass up the opportunity to save a life.”

|

|